The 1891 Great Shearers’ Strike in Queensland was one of the defining industrial battles in Australian history. Adam Adelpour draws the lessons

It was naked class war. The Queensland government deployed thousands of troops to break the strike. They used conspiracy legislation and dished out 100 cumulative years of prison time to strikers.

Thousands of unionists set up strike camps, amassed guns and ammunition, tried to derail trains—and many even talked about the need for revolution, civil war and socialism.

An excited editor of one republican newspaper said it would be better to “butcher every last squatter and member of this government” than concede defeat.

Looking back 130 years on, there are two lessons we can learn from this incredible strike.

First, it exposes the role of the state as an instrument of the ruling class and vindicates the argument that Marx had made 20 years earlier when he said: “The working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery and wield it for its own purposes.”

He argued that the state—the military, the police, the courts, prisons—was an instrument of capitalist class rule and must be destroyed to achieve working class democracy and liberation.

At the same time, the defeat of the strike played a significant role in the formation of the Australian Labor Party.

Union officials drew exactly the wrong lessons from the strike. Even today, union officials present 1891 as part of the origin story of the ALP: unions lost the battle but gained a clear understanding that parliament was the key to advancing working class interests.

With the growing prospect of an ALP federal government it is important to understand that the roots of the ALP’s reformism lie in despair at the prospect of workers winning through direct struggle.

Harsh conditions

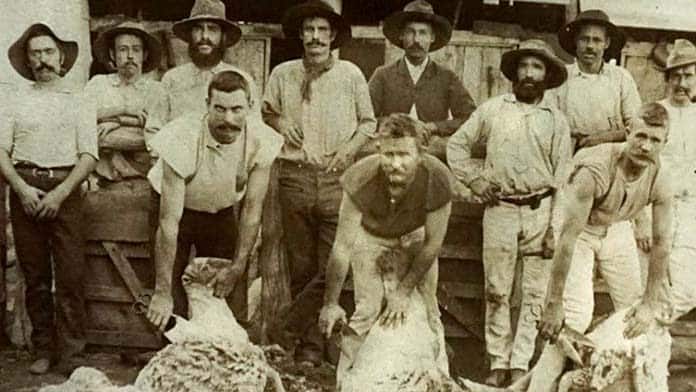

The story of the strike starts with the harsh working conditions in the booming pastoral industry. Wool was big business. In the 1860s Marx had described Australia as “a colony for growing wool”. By the 1890s, Queensland was exporting up to 45 million kilograms to Britain each year and pastoralists and bankers were making huge profits.

The industry was very concentrated and had immense political influence. About half was controlled by a dozen financial institutions. More than half the executive of the bosses’ United Pastoralist Association were members of the Queensland parliament. Every magistrate in western Queensland was a pastoralist.

Immense profits were built on the backs of thousands of pastoral workers, who toiled dawn till dusk and suffered diseases like trachoma and Barcoo rot. They slept in dirt-floored sheds on remote stations and could be fined for whistling or singing.

The 1891 strike took place following a period of growing union organising in the pastoral industry. Strikes were used as a direct weapon to force employers to improve conditions.

In 1887, the Queensland Shearers Union was formed in response to attempts to cut shearing rates. It fended off the cuts and forced pastoralists to employ shearers under union rules which included a closed shop (compulsory union membership for all workers). In 1890 the Australian Labour Federation (ALF) was formed and was involved in a dispute where Jondaryan shearers won a closed shop with the help of maritime workers who banned non-union wool.

In response, the pastoralists formed their own organisation. They were keen to pick a fight, as was the ruling class more broadly, because even though wool exports were growing there was an economic depression.

Their battering ram was a new shearing agreement that rejected the closed shop, cut pay between 15 and 33 per cent and rejected the eight-hour day. It also gave the employer the right to withhold wages until the end of the season and to refuse to pay if the labourer breached the agreement.

The union rejected the agreement and the strike was declared on 5 January. The pastoralists tried to get men to sign the agreement individually but station after station rejected it and formed strike camps. Employers began organising scabs (or “free labourers” as they called them). With the scabs came police and the army. Before February was over there were military forces deployed across western Queensland.

As the struggle escalated, the ALF desperately tried to get employers to agree to a meeting to arrange a compromise. But the employers were set on smashing the unions and refused to meet unless unions conceded “freedom of contract” (an end to the closed shop) first.

The central district shearers’ strike committee ignored the ALF’s calls for restraint and issued a statement in February saying if employers wanted a fight, they’d get it.

Major escalation

The day after the Barcaldine strike committee issued a general call-out of shearers, all its members were arrested. This signalled a major escalation. Because the pastoralists hadn’t pushed through the agreement everywhere all at once, the general call-out meant a massive increase in the number of striking sheds.

The ruling class was worried. There were strike camps often of hundreds with a section of each camp armed, huge street marches, public meetings and a high level of organisation among the strikers, who had public sympathy despite the hostility of the press.

At the Charleville camp, tents were arranged around streets with names like freedom, liberty and republic. The men took turns to cook. There was a daily meeting at 10am, signalled by a gun shot.

In Barcaldine, unions organised a vigilance committee which patrolled the town and arrested any drunk unionists running wild at night. One of the first May Day marches in the world took place on 1 May in Barcaldine. The Sydney Morning Herald reported that 1340 men took part, of whom 618 were on horse.

From the very start the government and pastoralists wanted to disperse the camps to break the strike. On 23 February, when military forces arrived in Clermont, the Governor-in-Council ordered strikers to lay down their arms and disperse. But strikers ignored the order and the government wasn’t game to enforce it.

Despite the press and some strikers talking about civil war, the overall union strategy was peaceful, mostly aiming to exercise the legal right to try to convince scabs to join the strike—what officials called “moral suasion”.

The government and employers used their huge military and police mobilisation primarily to keep scabs away from strikers so they couldn’t convince them to join. About 2000 soldiers and police, plus 1099 special constables, were deployed during the five months of the dispute.

In February, Major Landon Dealtry Jackson was sent to Clermont with three officers, 58 men, a nine-pounder field gun and a Nordenfelt machine gun. On 15 April, a cannon and a dozen artillerymen were sent to Charleville by government minister Horace Tozer. Pastoralists also tried to build private armies by recruiting vigilantes.

There were mass arrests—hundreds of strikers got a combined 100 years of jail time. Fourteen strike leaders were arrested, with 13 receiving three-year sentences. The Riot Act was used—once it was read anyone still in the area an hour later could legally be shot.

Throughout the strike the government, state officials and pastoralists colluded. This wasn’t hard as they were often the same people.

In February, Robert Ranking, the police magistrate in Rockhampton, contacted Tozer, telling him ammunition had arrived for both the union and a squatter. Tozer said to seize the unionists’ ammunition but to let the squatter’s cartridges through.

During the trial of the 14 union leaders on 9 May, Judge Harding said he would have shot the unionists if he was a police officer on the scene of the riot they had supposedly started. Railway Commissioners told railway workers they could be sacked if they attended pro-strike meetings or donated to strike funds.

The wave of vicious repression showed that, for the ruling class, their domination was far more important than the letter of the law.

Political conclusion

The scale of the repression, the lack of action outside the pastoral areas and insufficient funds all gradually wore down the strikers. They returned to work on 10 June but refused to formally concede “freedom of contract”.

Despite the role of the capitalist state, the political conclusion drawn by union officials and many strike leaders was that industrial action had to be replaced by political action and arbitration. If you couldn’t beat the state, you had to take it over.

The final manifesto of the strike committee concluded with a plea to register to vote so as to “reorganise society”. Three of the 14 conspiracy prisoners were later elected to parliament and one became a minister.

The Labor Party ran properly in Queensland for the first time at the 1893 election with a moderate program of reforms and an emphasis on opposing coloured labour. The first Queensland Labor Government took office in 1899.

The track record of the reformist and parliamentary strategy speaks for itself. In 1927, the Queensland Labor government smashed a railway strike. In 1948, during another railway strike, Labor ministers unleashed police on a march and beat Communist state MP Fred Paterson within an inch of his life. Federally, the ALP used the army to break the 1949 miners’ strike, the RAAF to break the 1989 pilots’ strike and the police to smash the NSW Builders Labourers Federation.

Parliament has turned out to be a road to nowhere. The dramatic gains in wages and conditions leading up to 1891 were won by militancy. Given it took the army and the police of an entire state to stop the shearers alone, it is clear the working class fighting as a whole would be unstoppable.