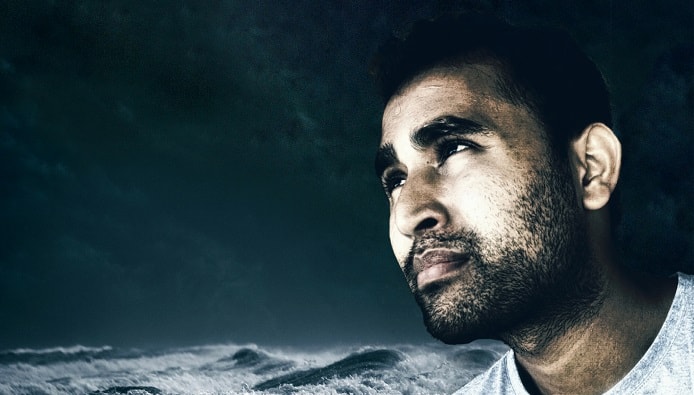

Escape from Manus, by Jaivet Ealom, is an incredible story of determination, cunning and sheer luck that tears apart the Coalition’s lies about refugees. It is a book you can’t put down—sharp and clear on the politics of Australia’s refugee cruelty.

It’s a book you will want to give to friends and family this Xmas and one I suspect that will eventually be made into a film.

The book starts with Ealom’s persecution as an ethnic Rohingya in Myanmar/Burma, where Rohingya are not recognised as citizens. He falsified documents to study at Dagon University in Yangon/Rangoon but without a national ID he could not graduate. He was taken on illegally as an industrial chemist intern but when that ended he had nowhere to go.

Meanwhile the regime had launched mass slaughter of Rohingya in the Arakan province, which saw his parents flee to the jungle. In danger, he is put in touch with Khaled, a Rohingya man who has fled to Jakarta, Indonesia, where a passport is not needed for travel. Ealom seeks to join him. He writes: “I took the first step. And just like that, I became a refugee.”

Ealom explains why the slur of “economic migrants” is so mistaken. “I had never met an economic migrant in detention. Most detainees had abandoned careers and all their worldly possessions, and fled rather than face imprisonment or death. By trying to reach Australia they were looking at life at a much lower socio-economic level than they had once known. That’s the opposite of an economic migrant.”

He also describes the pressures that lead refugees to flee Indonesia by boat. “Refugees were forbidden from studying, working or even opening a bank account in Indonesia—on pain of imprisonment … a few years after I left Indonesia, representatives from the UNHCR [the United Nations body with responsibility for refugee welfare] declared that refugees there, particularly single men, would be lucky to be resettled in two decades, if ever.”

Devil’s bargain

Ealom’s view of the UNHCR “as a paragon of justice and goodness” began to change in Indonesia. He points out the weakness of the UNHCR. “In each country where it operated it was essentially made to do a devil’s bargain. The choice was to take direction from the national government and its immigration policies or to take its people saving business elsewhere.”

Worse still is Australia’s long reach as a regional bully. Ealom shows how Australia funded a new passport system in the Solomon Islands in order to toughen regional borders. Australia also influenced Fiji to deny another Manus escapee, Loghman Sawari, the ability to make a legal claim for asylum, instead deporting him to PNG where he was placed in Bomana prison for daring to escape.

After almost drowning on one attempt to come to Australia by boat, Ealom makes it to Christmas Island. On his way he writes of his thinking about Australia: “A civilised country, with good people, What could go wrong?”

What could go wrong indeed. Ealom finds himself on the wrong side of former Labor PM Kevin Rudd’s 19 July 2013 announcement that “unauthorised maritime arrivals” would never be resettled in Australia. He is imprisoned first on Christmas Island then on Manus Island in PNG.

He writes of Christmas Island detention centre as “a summer camp imagined by machine with an unlimited bank account and little in the way of human compassion”.

“So much of this place was planned and deliberate. Architects had drawn up the blueprints, engineers had built the buildings, consultants had determined the staffing levels, and hired the workers. First world stuff. Yet when it came to the basic task of allowing us to use the pay phone: chaos … this was a callous stupidity that almost felt deliberate.”

He is given a wristband that says “EML 019”, his boat ID. “I didn’t know the wristband particularly mattered. It was made from itchy fabric, the kind you cut off after going to a live event. Now it was proving a durable irritant. The insistence of using letters and numbers instead of names was a classic ploy I should have recognised by now. In Burma I was forced to have my picture taken with a number plate and to call myself Bengali. Here I was EML 019.”

After arriving on Manus, a PNG government official reads the new arrivals a speech. “You were transferred here to be processed under Papua New Guinea law, by Papua New Guinea officials, to be resettled in Papua New Guinea if your claim to asylum is judge to be valid.” Ealom writes: “He ended his speech by declaring ‘you will never set foot in Australia’ … At a stroke he had given the game away. The line, if not the entire speech had been scripted by someone in the Australian government.”

Ealom points to similar Australian government advertising that states: “NO WAY: YOU WILL NOT MAKE AUSTRALIA HOME” and writes: “The irony of this approach, from a country that had been built on an invasion—a hostile takeover by sea, by white settlers forcing themselves on an unwilling Aboriginal population—was lost on the politicians.”

Rotten food

Ealom exposes the horrors on the PNG island of Manus, from the use of DDT (banned worldwide) but regularly sprayed through the detention centre, to constantly rotten food, overflowing toilets that force the men to wade through raw sewage, and the ban on mobiles to hide what was actually going on.

He demolishes then Immigration Minister and now Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s lies over the attacks on refugees that killed Reza Barati. When Morrison says: “I can guarantee their [refugees’] safety when they remain in the centre and act cooperatively with those trying to provide them support and accommodation,” Ealom writes that this was: “A pronouncement that deftly omitted the fact that those who were caring for us were also the ones who were killing us.”

He continues: “Most of the time, from what I had witnessed, people and the way they behaved were products of the power structures in which they operated. For the first time it seemed that an individual shared a unique portion of the blame. Scott Morrison appeared to relish the task of delivering his harsh and punishing policies.”

After a remarkable and daunting series of trials and tribulations, Ealom eventually makes it to Canada, where he receives very different treatment. A Canadian judge backs Ealom’s account, writing in a formal judgement: “You were held there for almost four years. During this time at Manus the conditions were intolerable, there was poor food, you were forced to sleep in shipping containers that were unbearably hot.”

Ealom damns Australia’s approach. “The government spent billions—billions—refining its merciless tactics, which were then repackaged and sold to the Australian taxpayers as plain common sense, packaged with a layer of false advertising about the urgent need to secure borders and save theoretical lives at sea.

“Meanwhile real lives were being destroyed. Refugees were locked up without charge, rebranded as transferees, their names swapped for numbers, as they were dumped in a third country to be terrorised indefinitely. How was that different from what was taking place under other dictatorial regimes?”

Escape from Manus graphically documents Australia’s refugee cruelty, which tragically continues today. Well over 200 refugees remain on PNG and Nauru, and around 70 Medevac refugees are still locked up in Australia after more than eight years.

The refugee movement has made many gains, but there is much more to change. As vaccination rates increase and Australia opens up, we will need more people in the streets to demand welcome, freedom and permanency for refugees.

By Chris Breen

Escape from Manus by Jaivet Ealom

Penguin, $34.99