On the eve of the outbreak of World War I, the British Cabinet was deeply divided. While Prime Minister Herbert Asquith was for war against Germany, a large proportion of the Cabinet members were fiercely opposed.

The crisis ran so deep that on August 3, 1914—the day before Britain declared war—four Cabinet members and a junior minister resigned.

It was a close run thing. Britain at least considered, as the USA was, remaining neutral.

What was Australia’s role in this finely balanced situation, as the Cabinet wavered and anti-war protests took place in London?

The response from Melbourne—the then home of the federal parliament—was unambiguous. Australia was for war.

More than that, Australia vied with New Zealand and Canada to be the most loyal and most belligerent province of the Empire. The offer of its navy and an initial detachment of 20,000 troops was made well before the final steps to war in Europe had been taken, and while the British Liberal Party government was still split.

While it would be an exaggeration to say that Australia tipped the balance, the British pro-war press and the Liberal Imperialist faction of Cabinet used its offer of support to undermine the neutralists’ position. As one Conservative MP put it: “Our great victory [in the war of public opinion] was won when Canada and Australia and New Zealand came in with us.”

Australia’s offer was all the stronger as it was made by Joseph Cook’s Commonwealth Liberal Party and endorsed by Labor in the midst of a federal election. Whoever was to win, Australia was committed to the war effort.

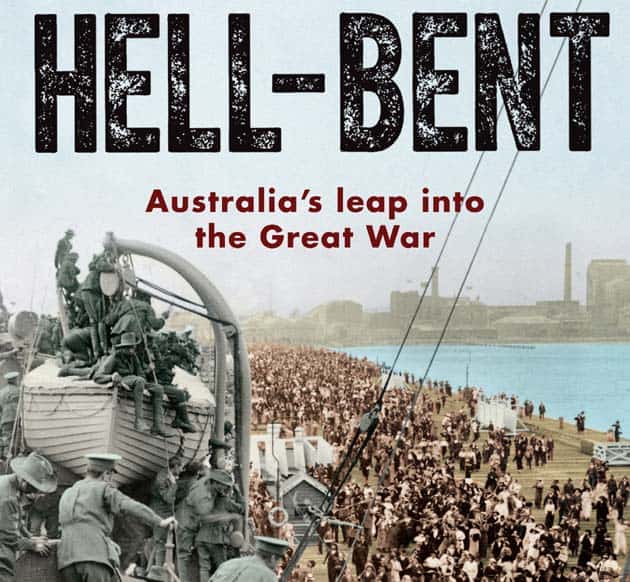

This is the story told by Douglas Newton in Hell-Bent: Australia’s Leap into the Great War.

Labor’s response was not an aberration. In 1911, French and German interests collided in Morocco, leading to fears of war. Labor Prime Minister Andrew Fisher promptly agreed to transfer RAN ships to the British navy and mobilise troops if a conflict began. He did the same again the next year as the First Balkan War raised fresh tensions.

In late 1913, now back in opposition, Fisher was reported by a visiting British minister as making “loyal and patriotic speeches of an Imperialist kind” as “the fear of Japan has brought a lot home to them”.

So Labor’s determination to ensure that no one could put a cigarette paper between its position on WW1 and the Liberals’ was no surprise. This was the context for Fisher’s infamous declaration, in Colac on July 31, that “Australians will stand behind our own to help and defend her to our last man and our last shilling”.

Why was the British Cabinet divided, given that all its members were committed to defending and extending the British Empire? It’s an obvious question, but one which Newton answers only in passing.

The neutralists were concerned that Britain’s agenda was being dictated by France and Russia and that a ground war in Europe would be a distraction.

Lord Lamington argued: “Our interests are primarily world-wide and not merely European [and] the safety of India and of our dominions are of far greater importance to us than a possible defeat of France.”

The imperialist faction worried that a German naval attack on the northern French coast would ultimately threaten Britain’s ability to protect its global trade. Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey told parliament that if Britain did not help defend the French coast, the French would withdraw its fleet from the Mediterranean. This in turn might embolden Italy to threaten British trade routes to India and beyond.

The division, in other words, was about means rather than ends. Most neutralists fell in behind the imperialists once war was inevitable.

On one thing they were easily agreed—war with Germany was an opportunity to seize colonies. This would be both a task for the dominions and a reward.

The Committee of Imperial Defence in London had already agreed in 1913 that Australia should occupy “hostile bases in the Western Pacific”. Australia’s military chiefs drew up plans to take New Caledonia, the New Hebrides, German New Guinea, Dutch New Guinea, Timor, Java and Papua, along with cooperation with India in Sumatra, Borneo and the Philippines.

While the British ruling class may have been divided over the best way to defend its empire, its Australian counterpart was united in understanding that eager cooperation with Britain was its best strategy for maintaining a white colonial outpost in Asia.

Australia’s enthusiasm to join the impending war in 1914 was to find its echo in its demand to be invited into later wars in Vietnam and Iraq. It also provides a historical context for Bill Shorten’s me-too approach to the conflict with ISIS.

By David Glanz

Hell-Bent: Australia’s leap into the Great War

Douglas Newton

Scribe

RRP $32.99