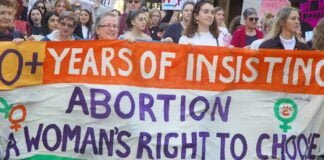

“There’s something wrong with the world if a woman can make more money as a Play Boy bunny or a cover girl than as anything else!” So argues a women’s liberationist at the one of the US women’s movements biggest ever protests, in Washington, 1970.

These days, some women run countries or companies—but for the vast majority, this statement is still true. That illustrates how much sexism, if more disguised and insidious, is still with us.

She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry, originally released in 2014, has played to dozens of sold out screenings in Australia, and is now streaming on Netflix.

Aiming to provide a comprehensive history of the women’s movement of the late 1960s and 70s in the US, it features fascinating original footage from protests and meetings of the movement in the 1960s and 1970s. Women activists, including famous figures such as Rita Mae Brown, Susan Brownmiller and Jo Freeman, reflect on their experiences in the movement while we watch their younger selves in action.

Despite the thoughtless title, She’s Beautiful also seems designed to address the issues concerning today’s intersectional feminists, taking on questions of race, sexuality and class and organisation. Ultimately, though, the attempt to explain the movement’s debates is rather superficial. Determined to wrap everything up in a neat bow, it ends up being very forgiving of the issues that contributed to the movement’s decline in the 1980s.

Lighting the fire

Changing conditions in Western capitalism set the scene for the movement. The post-war boom drew more and more women into the workforce. Yet the prevailing view remained that a woman’s place was in the home. Women were unable to obtain credit or bank loans without a husband’s approval.

The need for a more skilled workforce meant higher education was expanding, and increasing numbers of women were graduating from university. But women were still denied jobs they were qualified for, or drastically underpaid for them.

One activist in the documentary recalls a job advertisement for a university-educated woman secretary—one of the attractive possibilities included in the advertisement was that you had the chance to end up the boss’s wife!

And at the same time, the pill dramatically transformed sex and relationships, giving women and their partners the opportunity to control when—and if—they had children. As Judith Orr observes in her new book, Marxism and Women’s Liberation, “Up until then, contraceptives … were often too expensive for most working class pockets. The alternatives were early withdrawal or sponges soaked in brandy or vinegar.”

Combine this with thousands of women organising in the Civil Rights Movement from the mid-1950s, and you can see how the situation was explosive. Many of the women interviewed attest how the Civil Rights movement gave them their “training” in left politics, and how activists like Diane Nash, who led the 1961 Freedom Rides, showed them the possibility of women leading political struggles.

Conscious beginnings

Women faced sexism from within the radical movements, particularly in the US. Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), which was leading the student wing of the movement against the war in Vietnam, rejected an anti-sexist motion from women members in 1967. Popular slogans demonstrate what was considered acceptable—one encouraging men to resist the draft was “Girls say yes to boys who say no”.

Women formed their own organisations and began “consciousness raising” groups to discuss issues they faced, calling themselves “Women’s Liberation” after the National Liberation Front fighting the US in Vietnam.

Here began the famous slogan “the personal is political”. On the one hand, this meant women generalising out of personal experience of sexism to try to understand it as a problem of society. On the other, it also led to seeing personal transformation or “living the revolution” as the key to change.

The Miss America protest in 1968—where a Women’s Liberation banner was unfurled on national TV and a sheep was crowned the winner by the protestors—was the movement’s first major protest and it provoked nationwide discussion.

In archival footage, one TV interviewer, shocked by the notion, asks a group of women activists, “So this group doesn’t think a woman’s place is in the home?” Kate Millett (who coined the term “sexism”), responds, “We believe in the political, social and economic equality of the sexes … we’re an oppressed group.”

The movement flourished and groups formed all around the country (and around the world).

An issue of class

In the early years, there was more focus on demands that concerned working class women—in particular equal pay, free abortion and child care. The 1970 demonstration in Washington was organised as a “strike” around the slogan, “don’t iron while the strike is hot” and had three main demands:

- Equal opportunity in health and education

- Free abortion on demand

- 24-hour child care

Talk of revolution was everywhere, with radical movements shaking up society from East to West. One woman explains, “We believed we needed social revolution for women to be truly liberated … We didn’t want a piece of the pie. We wanted to change the pie.”

But many women saw what needed to be overthrown not as capitalism, but “male supremacy”. Anti-Communism in the US, along with the conservative gender norms of Stalinism that influenced the Communist organisations meant that socialist influence in the movement was weak.

Instead, various forms of patriarchy theory dominated. As Orr explains, the idea of patriarchy can be summed up as, “a system of control and domination that pre-dated and acted alongside and separate to class society, by which all men oppress all women.”

Men were the “political enemy”, akin to slave owners, “the foremen in the big plantation of maleville”, according to one famous movement document, the Florida Paper of 1968 written by Beverly Jones and Judith Brown. Others said women were a colonised fourth world and class was essentially a distinction between men.

Though this is not explained as such, the film does mention one manifestation of this approach—the idea that women needed to stop having sex with men to be truly liberated. In one clip, Jill Johnston claims, “all women are lesbians, except those who don’t know it.”

However, the movement also faced homophobic ideas on its right, particularly associated with Betty Friedan and the lobby group, National Organisation of Women (NOW). Friedan argued lesbian issues were a diversion; a “lavender menace”. In fact the movement was often blind to issues outside the experience of the white, university-educated women who formed its core—another issue was the different priorities of black women and white women.

Abortion was a key concern for Women’s Liberation groups, and backyard abortion was still killing women across the country. In one attempt to address this, an underground abortion service in Chicago performed 11,000 illegal abortions from 1967 to 1973.

But many black and Latino women felt their needs were different. Black women faced involuntary sterilisation, documented by civil rights activists in the book Genocide in Mississippi, as had Puerto Rican women. Understandably, many saw their right to have children as more important than abortion. And in a situation where black men were beaten and harassed by police, many black women rejected the movement’s idea of all men as the problem.

The resolution was often for black women to form their own organisations (though, as the film notes, this was rejected by the radical women of the Puerto Rican equivalent of the Black Panthers, the Young Lords).

Fragmentation around identities was accompanied by an increasingly inward-looking focus on lifestyle. One group, Cell 16—featured in She’s Beautiful—had a program of “celibacy, separatism and karate”.

She’s Beautiful presents the debates as almost an entirely positive experience, often accepting the division of the movement into multiple organisations based on separate identities as the solution, and downplaying the acrimony the debates produced.

The alternative to this process of fragmentation was uniting women and men against the capitalist system that is the source of sexism and oppression, on the basis of class.

It is much clearer today—with Hillary Clinton angling for the White House—the way that class cuts across women’s experience of oppression and their interest in fighting it. As one black feminist activist, Eleanor Holmes-Norton, explains in She’s Beautiful, “Women who have spent their lives working in other women’s kitchens have a different kind of handicap than women who have been oppressed for their sex in other ways.”

In the 1970s women’s movement in Australia and Britain, some activists had more of a socialist perspective and saw men as their comrades in the struggle against sexism. Such an orientation meant, for example, mass demonstrations for abortion rights that involved tens of thousands of men marching alongside women.

As Orr and others have demonstrated elsewhere, while some working class men accept sexist ideas, they don’t have a stake in them. Sexist ideas both divide the working class and provide the ideological justification for unpaid labour in the home—something that benefits the capitalist class, not working class men. Winning women and men away from sexist ideas is part of the struggle of the whole class.

The women’s movement and the struggles of the 1960s and 70s achieved much in transforming sexist attitudes and in basic equality for women under the law. She’s Beautiful is bookended by the contemporary challenges of sexism in the US—constant attacks on abortion rights and SlutWalk protests. We can celebrate the achievements of the women’s movement, but if we’re to deal the final blow to a sexist system, we need to learn also from its mistakes.

By Amy Thomas

She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry

Directed by Mary Dore

Now on Netflix