The Hunger Games

Directed by Gary Ross

In cinemas now

The Hunger Games is the latest addition to a string of political Hollywood films produced over the last few years. But unlike films such as Tower Heist and Rise of the Planet of the Apes, the film adaptation of Suzanne Collins’ first book in The Hunger Games trilogy, is far more complete in its condemnation of the capitalist system.

It’s set in a post-apocalyptic North America; a fascist dictatorship ruled from the affluent Capitol. This dystopian future is a striking allegory for capitalism in decay. The sharp class divide between the wealthy Capitol and the 12 districts that surround it is presented not only through a vivid contrast between the lavish extravagance of the rich and the destitution of the poor, but as an exploitative social relationship between rulers and producers. The Capitol lives not in spite of, but directly on top of the remaining resources of the world, which are laboured on by the working class in districts like District 12.

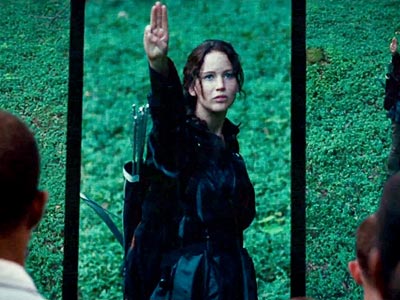

It’s from District 12 that protagonist Katniss Everdeen is conscripted by the regime as a “tribute” to compete in an annual death match between teenagers from other districts, “The Hunger Games”. The annual “reaping”, at which two teenagers are ritualistically sacrificed from each of the twelve districts to compete in the Games, is reminiscent of Holocaust films and their portrayal of deportations to death. The Games are a penance introduced by the regime to reconcile the districts to their rulers following an uprising 74 years ago.

Like fascism in real life, the system needs these dictatorial measures to maintain its rule over a restive and unsatisfied population.

Alliances between “tributes” form along class lines in the Games. Privately trained, groomed-to-win kids from the wealthy inner districts unite against the children of the poor, outlying districts. But Katniss and her fellow tribute Peter from District 12 find in the Games (warning: spoiler ahead!) an outlet for challenging their own powerlessness at the hands of the regime in their defiance of the odds.

In a refreshing contrast to teen sensations like Twilight, the film is daring in its willingness to break with portrayals of women as passive subjects. Katniss is not only a woman protagonist, but also a strong one and a hunting pro. Her relationship with Peter is not primarily a morality tale of teen love, but a political act of protest against the regime.

Ugly reality

The film constantly juxtaposes the seeming stability of bourgeois normality in the Capitol with the dark underbelly of capitalist exploitation and succeeds in illustrating just how sickening it can be. The over-the-top clothing, furnishings and lifestyles in the Capitol evoke the decadence of Marie Antionette and the French monarchy—or their modern incarnations in characters like Donald Trump, Richard Branson or Australia’s own Rineharts, Murdochs and Packers. Katniss is amazed by the sheer amount of luxurious food in the Capitol after years of constant near-famine in her district.

The whole set up of the Games draws on reality television, and the Game “arena” is not at all unlike the fake reality of The Truman Show. It seems a conscious imitation of the look of shows like Big Brother and Survivor and a comment on how anaesthetised capitalist culture is to violence and competition. The broadcasting of the Games is both a focus for nationalist fervour and a mechanism of social control, intended to sow a sense of disempowerment amongst the masses in the districts.

But perversely, as Capitol’s President Snow tells a minion, it also introduces a faint sense of hope, of beating the odds, of making it—and that faint hope is useful in tying people to the regime.

Yet underlying the horrific spectacle on show, the possibility of resistance and struggle against tyranny is a constant undercurrent in the film. In the arena, Katniss allies with Rue, a 12-year-old from the extremely oppressed and mostly black agricultural plantation, District 11. After her murder, a shot of District 11 breaking out into a riot, and police water cannons dispersing demonstrators, evokes a parallel with the Occupy protests or the streets of Greece or Egypt of today—and hints towards the possibility of a different future.

Jimmy Yan