A new exhibition in Melbourne celebrates the constructivist art that emerged out of the Russian Revolution.

Artworks by Australian artists sit alongside those from Russia, continental Europe, England and Argentina, tracing the influence of constructivism over the last century. The movement continues to inspire artists today.

This exhibition is one of the many around the world marking the centenary year of the 1917 Russian Revolution, a defining time for art.

Before going to the exhibition I wondered whether the works would reflect the dynamism of revolution and whether the later works would fit with the original artists from revolutionary Russia.

It became clear in the combined works of the exhibition how the two women curators, Sue Cramer and Lesley Harding, applaud the revolutionary artists’ aspirations for a better future. Works by the great names in Soviet art, such as El Lissitsky, Vladimir Tatlin, Kasimir Malevich, Alexender Rodchenko, give a feeling for the time of openness and creativity following the revolution a century ago. Placing them alongside other works through the last century helps show their influence internationally on art through to today.

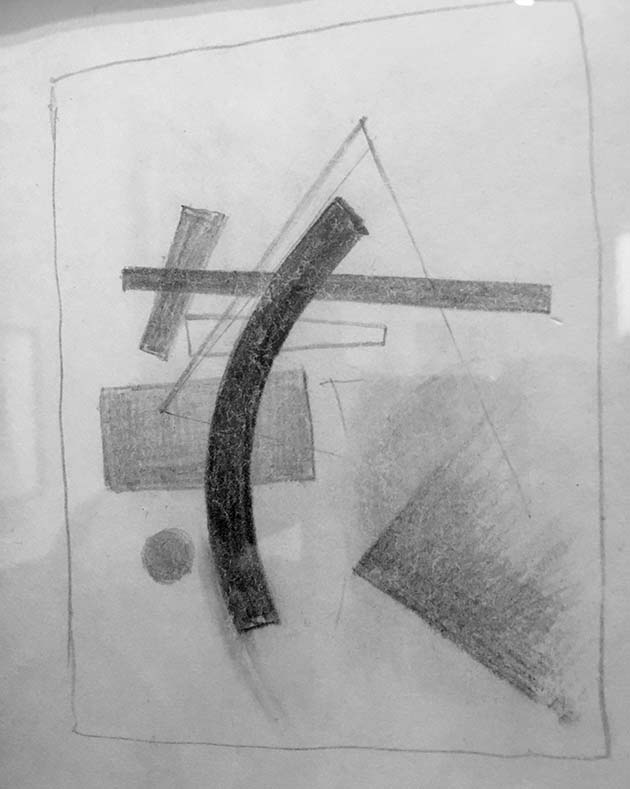

Constructivism built on earlier forms of avant-garde art, experimenting with abstract designs and new industrial materials. At its core was a deeply motivated conviction that the artist could contribute to the material and intellectual needs of the whole society by engaging with architecture, building, graphic design, photography, theatre, and clothing design.

Their aim was not simply political art but art that served the whole society. The constructivism threw themselves into the service of the revolution and its aim of constructing a new society.

After the revolution in 1917 artists of the constructivist era designed festival decorations, posters, brochures, painted buildings, trains and ships, made films and photographs.

Among their proposed designs was Tatlin’s famous tower, intended as a working headquarters as well as a monument to the Third International. It was never actually constructed.

Constructivism shared with other modern art movements a belief in geometric abstractions as representing modernism and optimism for the future. They threw out the constraints of tradition, with abstractions and blank forms representing the exhilarating void of the unknown and a springboard for the imagining of new tomorrows.

The curators bring an integration of ideas across the various art forms, and show the strong role taken by women artists who, because of the revolutionary period, were playing a more active role. The later works represent women artists well too.

Subversive

To many critics in the 1920s modern art was dangerous, as a result of its association with Communism. The New York Times, for example, reprinted an article on the subject in their 3 April 1921 edition. The Reds in art, as in literature, they wrote, “would subvert or destroy all the recognized standards of art and literature by their Bolshevist methods”.

The Heide Exhibition is a reflection on the importance of constructivism for many Australian artists.

Australian photographer Wolfgang Sievers’ The Gears 1967 is rooted in the early constructivism. Although his work shows a movement away from the political implications of the revolution, the simplicity of the abstract constructivist forms remains. Max Dupain’s Pyrmont Silos 1933 is a perfect example of the forms, shapes and shadows in the formal abstraction of constructivist art.

Sue Cramer argues that constructivism still has a particular relevance today because, due to developments in global politics, “people are looking at different ways to create a better world”. This emphasis makes for a dynamic selection of artists internationally and from Australia who are developing the original aims of constructivism.

Constructivism though separate from the revolution has at its core the idea that anyone can be an artist and that art is a part of life.

Among the leaders of the Constructivist movement were painters such as Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, the son of a maid and a shoemaker, and Gustav Klutsis, from a peasant background. There’s also the artist who invented photomontage, Pavel Filonov—the sixth son of a cab driver.

You don’t have to know about the concepts or the history to just go along and immerse yourself in the beauty and the intriguing, cups, broaches, plates, film, paintings, clothes and sculptures.

The catalogue, which lists all 233 works, is a useful companion to the show. The call of the Avant-Garde: Constructivism and Australian Art is on at the Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne from 5th of July till 8th October and is worth the visit.

By Melanie Lazarow

Call of the avant-garde: Constructivism and Australian art

Heide Museum of Modern Art

Until 8 October