The recent rape scandals highlight the need to smash a system that reduces women to sex objects and unpaid carers, writes Ruby Wawn

In the past month, the Liberal Party has been rocked by a series of sexual assault allegations.

The party was exposed as covering up the rape of former Liberal staffer Brittany Higgins in her parliamentary office by a male colleague in 2019. Then Attorney-General Christian Porter was accused of raping a 16-year-old girl in 1988.

This has led to women all across society speaking out about their experiences of rape and sexual violence, including hundreds of accounts from women of abuse while teenagers at school.

There is no doubt that sexism is an everyday reality for women. One in three women in Australia has been harassed or assaulted at work. One in six women has experienced at least one sexual assault by the age of 15.

But what can be done to stop this?

The most common response has been to call for more consent education at schools and improved reporting procedures at work.

But this fails to get to the heart of why rape and sexual violence remains so widespread.

Our society is so saturated with sexism that simply running consent classes will have little impact. And consent education individualises the problem as a result of male attitudes.

Rape isn’t a result of men’s insatiable sexual needs or instincts—most men don’t rape or murder women. Nor is it due mainly to “stranger danger”—the majority of women experience sexual violence at the hands of someone they know.

Sexual assault is a product of a society where sexuality and sex are a commodity that can be bought and sold.

All around us women’s sexuality is subjugated—we are told women’s self-worth derives from their relationship status and ability to conceive children, women are sexualised and used to sell us things, while pornography objectifies women.

This is reinforced by common narratives of rape—that women are raped because they were drunk or dressed provocatively and that men can’t control themselves.

These ideas are promoted and perpetuated by major social institutions like the mainstream media, advertising, entertainment—and by governments like Scott Morrison’s.

The view of women as submissive and valued mainly for their sexuality is a product of women’s role in the family—an institution that is of massive benefit to capitalism.

The system relies on the unpaid work done by working class women in the home to raise the next generation of workers. Women are expected to play the role of mother, raising the next generation of the productive working class, while men go to work to provide for their partners and children.

The nuclear family underpins these “common sense” sexist ideas—that women should be the primary caregiver, that women should do most of the domestic labour and that women are innately more caring.

These ideas are constantly reinforced from the top of society—that’s why men like Christian Porter campaign around “family values”, why ideas that challenge traditional gender roles like the Safe Schools Program face virulent attacks, why homophobia exists and why women are constantly objectified and sexualised in the media.

The Liberals have also brought down a barrage of sexist policies that make it harder for women to escape this.

At the whim of One Nation, none other than Christian Porter recently dissolved the Family Court, the only specialist court where families and women experiencing violence and relationship breakdowns can turn for legal redress.

The Liberals also privatised 1800RESPECT, a national telephone and online counselling service for victims of domestic violence and sexual assault.

Callers are now triaged by call centre staff, not trained counsellors. Natalie Lang, NSW secretary of the Australian Services Union, called it a “McDonald’s drive-through approach to counselling” which aims to reduce costs and increase profits.

Domestic violence services in Australia are also chronically underfunded.

Domestic Violence NSW chief executive Joanne Yates says that every year three out of four women who access homelessness services are fleeing violence. But at least 150 women are turned away each day by underfunded services. Despite the government promising a $150 million funding boost to domestic violence services, much of the sector is yet to see the funds.

The Liberals are even slashing funding for what Scott Morrison describes as “skin curling” sex education taught in public schools which aims to “address and prevent family violence, through the examination of topics around gender, power and respect”.

This comes as more than 3000 girls and young women have recently provided testimony about being sexually assaulted by teenage boys.

Benefiting capitalism

But there’s nothing innate about the traditional gender roles we experience under capitalism. In pre-class societies, women played a much more equal role both economically and politically.

Capitalism reinforces these sexist ideas because the ruling class is unwilling to pay for services like child care, aged care, disability care, cooking, cleaning and laundry.

Instead, women step in to provide this in the home at as little cost to the system as possible. Where we have won such public services, the logic of neo-liberalism means that they are limited, privatised and under constant attack.

It is estimated that the unpaid labour associated with childrearing saves the Australian state $345 billion every year.

Given that Australian families spend on average 30 to 40 per cent of their income on childcare it is often difficult for both parents to work full-time. And it is nearly always the lower-paid woman that stays at home to look after the family.

The rising cost of living means that most women also work outside the home.

Women now make up 47.2 per cent of all employees. But they are also more likely to be insecurely employed, making up 67.2 per cent of all part-time employees and on average earning 13.4 per cent less than men.

Casualised and insecure work leaves women vulnerable to assault and harassment, both in the home and in the workplace. Wage disparities and casualisation mean women are more likely to be economically dependent on their partner and lack the financial ability to leave unsafe relationships or speak up about harassment in the workplace.

Our taxation system even discourages women from working more than three days a week, with women losing up to 90 per cent of their wage for every extra day they work and use childcare.

In many cases it actually costs women money to go to work. But childcare workers themselves, who are over 90 per cent women, earn well below the national average and on average as little as $23 an hour.

Ruling class women can afford to outsource domestic tasks like cleaning and childcare to low-paid, working class women.

They are also unreliable allies in the fight for women’s liberation. It was two female ministers, Linda Reynolds and Michaela Cash, who covered up Brittany Higgins’ rape in parliament.

Australia’s richest person, Gina Rinehart, who earns $600 a second from the mining company she inherited, has lamented not being able to pay workers $2 an hour.

And it was our first female prime minister, Julia Gillard, who cut access to the Single Parenting Payment, forcing more single mothers to live on the dole.

Sexist ideas clearly exist among working class men as well. But men aren’t born sexist: they learn sexist ideas from the world around them. As Karl Marx said, “The ruling ideas in society are the ideas of the ruling class.” And sexism is constantly pushed by the ruling class.

Like other ideologies such as racism, sexism is designed to divide the working class and keep us under control.

Sexism also affects men. Men feel the pressure to fill the traditional male breadwinner role. When working women earn less, men have to work more to make up for the difference in income.

In his 2019 International Women’s Day address, Scott Morrison claimed that the rise of women shouldn’t come at the expense of men.

But working class men don’t get paid more because women get less. The only people pocketing money from the gender pay gap are the bosses.

United struggle

We all have an interest in fighting for the material conditions which can liberate women.

Men have the potential to be our allies in the struggle against the system and to join us in the fight against casualisation, for equal pay, for free childcare and to liberate women from the confines of the home.

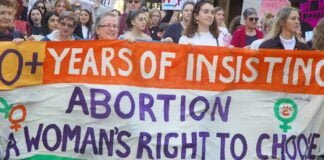

At the height of the women’s liberation movement in the 1960s and 1970s, men and women fought alongside each other in strikes over equal pay.

In 2019 workers at Chemist Warehouse went out on strike over casualisation and sexual harassment in the workplace and got sexist managers sacked.

In October 2020, men in Poland joined women on strike for abortion rights.

We must call for an independent investigation into the allegations against Christian Porter, we must call for him to stand down and we must call for increased funding for services for survivors of sexual violence.

But these things alone won’t solve sexism.

We also need to fight for reforms that will have an impact on women’s lives right now. We need to fight to increase JobSeeker so that women and families aren’t forced to live in poverty.

We must fight for secure employment so that women feel confident to speak up about unsafe work conditions.

We must fight for proper funding and against the privatisation of health, disability and aged care.

And we must fight for a system that doesn’t have sexism hard-wired into it.