The right to accident pay, or workers’ compensation, was only won after a major strike in 1971 that united unions across the construction industry, explains Tom Orsag

The COVID-19 era has shown how little many bosses care for workers’ health and safety. A mass strike 50 years ago is a reminder that workers can rely only on their own struggle to defend their lives and livelihoods.

Imagine a developed country where accident pay, or workers’ compensation, is pitiful and inadequate. That country was Australia in early 1971.

May of that year saw a mass strike of 35,000 NSW building workers of all construction unions—trades and labourers—for a decent workers’ compensation scheme in their industry.

The smashing victory opened the floodgates for workers in other industries to follow. And it all started with a strike in one workplace.

A year earlier, the NSW Builders Labourers Federation (BLF) won a pay rise after a five-week strike led by a new left-wing leadership elected in June 1968.

Builders’ labourers saw their pay rise from 75 per cent of a tradespersons’ wage to 90 per cent.

The 1971 accident pay strike would be the BLF’s second mass strike in two years. Importantly it would pave the way for the members of the BLF supporting Green Bans soon after.

As Jack Mundey, secretary of the BLF and member of the Communist Party of Australia (CPA), wrote, “I believe if we hadn’t won the big strikes of ’70 and ’71 … lifting up the second-class status of builders’ labourers … this support [for Green Bans] would be far less.”

The BLF’s 1970 pay rise victory inspired tradespersons, principally in the Building Workers Industrial Union (BWIU) made up of carpenters and bricklayers, to fight for a pay rise themselves.

Emerging as a concurrent issue was the demand for improvement to the pitiful NSW state workers’ compensation scheme, by builders making direct payments of “accident pay”.

The BWIU was led by nominally left-wing union officials, who would later be part of a pro-Russia split from the CPA in 1971. The union had not led a major strike since 1957 despite the massive post-war boom. The union liked short strikes, if none at all.

Complex

The building boom of the 1950s and ’60s had led to taller and taller buildings, complex new ways of working and a rise in workplace accidents.

1971 saw the start of the Centrepoint Tower, the new Sydney Hilton Hotel, the CAGA centre, office buildings in Walker Street, North Sydney, and a $20 million (in 1971 dollars) extension of the Royal North Shore Hospital.

NSW compensation figures for injuries that resulted in three days or more off work showed that building, construction and maintenance accounted for almost one in five, despite the industry employing only 9 per cent of all workers.

In three years, an appalling toll of more than 61,000 compensation cases—some fatal, others creating permanent disabilities, others lesser but still cruel—occurred in the NSW building industry.

In April 1970, all ten construction unions combined in a body called the Building Trades Group (BTG) and launched a campaign for what they called “accident pay”.

Builders, like all employers, relied on the state government, in the form of workers’ compensation, to meet their obligations to injured workers. The BTG now insisted that building companies provide “accident pay” to meet the shortfall between the award wages and workers’ compensation—“compo”.

Jack Mundey wrote, “At the time compensation law was fairly complicated, being based on a formula which meant an injured worker would get about 75 per cent of his or her normal weekly wage.”

Workers’ compensation was deliberately held low by the NSW Liberal state government of Robert Askin. Injured workers were often forced into debt.

The Askin government also encouraged the employers’ Master Builders Association (MBA) to stand firm against the accident pay claim.

Joe Owens, assistant state secretary of the BLF, said, “It is high time builders accepted responsibility and made up the compo payments to award wages. Their balance sheets show they can well afford it.”

Individual sites took strike action for an accident pay top-up, such as a Chillmans job in Sussex Street in February 1970 and another at Mogul Construction in North Sydney, where the job delegate argued they were “the first workers in Australia to win full accident pay”. These “spontaneous” strikes came from rank-and-file leadership and initiative.

Struggle

Rank-and-file, site-by-site action in early 1970 paved the way for the broader mass strike of 1971.

In February 1971, a BTG mass meeting carried a resolution for a $6 per week pay rise for trades and a resolution demanding all employers in the industry agree to “full accident pay”, noting that three employers had already agreed to this.

Jack Mundey wrote, “The campaign was taken up by the BWIU. We had some initial disagreements with them. The more ‘craft-conscious’ tradesmen in their membership wanted to jack up their wages beyond the 100:90 ratio and we disagreed. Nonetheless we supported their struggle for accident pay.”

Mundey and the BLF understood they could not stand aside from the accident pay issue in a sectarian manner, as it affected their members.

The issue bubbled along as site-by-site action with no real lead from the BWIU’s leading officials, Pat Clancy and Tom McDonald.

Then on Monday 3 May, a BWIU organiser went to the flagship project of the era—the Sydney Opera House. He led a march of BWIU members across Sydney Harbour Bridge to the offices of Hornibrooks, the main contractor, in North Sydney. The union’s officials were taken by surprise when their members declared their strike was indefinite.

The BWIU officials felt they had to call a mass meeting for the following Monday.

Pledge

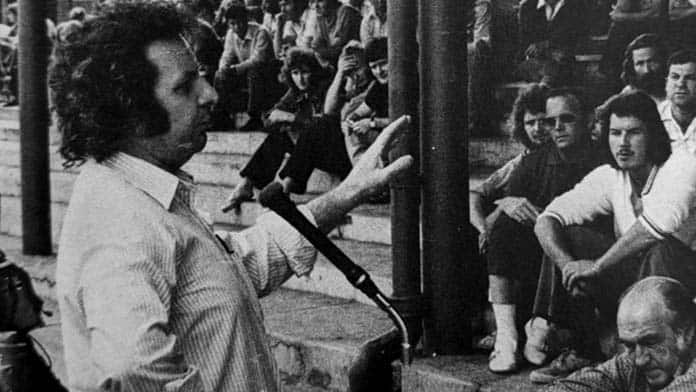

Jack Mundey wrote, “The following Monday I attended a mass meeting of the BWIU [as it was a BTG action]. I told the tradesmen that the builders’ labourers supported their claim for accident pay. We would also support their claim for higher wages, provided our ratio was maintained. But whatever happened to the wages issue, we would join the strike by Friday, unless the accident issue was settled by employers.”

Mundey made good his pledge when an all-unions BTG mass meeting was held on Thursday 13 May at Wentworth Park, Glebe. It was the principled thing to do: the Sydney Opera House site employed between 300-400 builders’ labourers, who would have been scabbing on the BWIU if they continued to work.

About 3500 building workers went to the mass meeting, with only two dozen voting against the resolution for an industry-wide strike for accident pay.

The union members then marched, some in wheelchairs, from Wentworth Park to the MBA offices in Newtown, where a noisy demonstration was held.

Mundey wrote, “And so on Friday, we were all on strike right through the industry and stayed out for three weeks.”

Tensions emerged between the BWIU’s top-down leadership and the BLF’s encouragement of rank-and-file initiative and picketing.

Previous BTG practice had been that voting strength was roughly equal to a union’s membership size but now the BWIU insisted that each of the 10 unions had one vote each. This meant that a union like the Stonemasons with 300 members would carry the same weight as the BLF with its 9000 members.

Clancy moved to end the strike. In its third week, he met Judge Sheehy of the State Industrial Commission, who promised to hear the accident pay case in one day if the strikers returned to work.

On that basis the BTG drew up a recommendation for a return to work, which was carried at a BTG meeting nine votes to one, with the BLF against.

A mass meeting of construction workers in Sydney voted for a rank-and-file motion to stay out for another week but the BTG officials tallied votes from across the state and declared a dubious majority of 63 per cent for a return to work.

Challenge

The belief that a better accident pay outcome could have been won if workers stayed out for longer was borne out the next day. While Sheehy granted the BTG’s claim for accident pay loading, he limited it to six months, a blow to seriously injured workers.

Immediately, a large group of builders took legal action in the Supreme Court to block the decision. They lost their challenge in October but that was enough to prevent accident pay coming into effect until December.

While Jack Mundey was head and shoulders above almost all union leaders in Australia, he was still trapped within his role as a union official and had not encouraged independent rank-and-file organisation inside the BWIU as a counter to Clancy’s machinations.

Despite the setbacks, the accident pay strike was a defeat for the employers—and their media mouthpieces knew it. The Financial Review moaned, “The revolutionary character of the NSW building workers’ claim is what accounts for the strength of employer opposition, and, of course, for the enthusiastic support of other unions.”

While the Sydney Morning Herald wrote, “A breakthrough by the unions in obtaining their demands of full pay for building workers off duty through injury could open the flood-gates to other industries.”

Their fears were justified, with accident pay becoming available for all NSW workers and then those in the rest of Australia.

If workers today want decent health and safety the lesson is clear: they need to fight for it.