In 1968 the world was shaken by mass revolts in country after country, giving birth to a new radical left, writes Miro Sandev

1968 is stereotypically depicted as the year of sex, drugs and rock and roll. Images of long-haired hippies and rebellious students are shown, as if the whole turmoil was just about privileged children “acting out”.

But it was a time when regimes that had seemed like immovable monoliths began to crack and were on the verge of being completely smashed by movements from below.

Workers and students shook the foundations of capitalism, both in the West and also in the supposedly “Communist” Eastern Bloc. By the end of the year a host of historic movements had been born, the Vietnam War had decidedly turned against the US, Stalinism was dealt a hammer blow and socialist revolution once again seemed on the cards in advanced capitalist countries like France.

In January the world’s greatest superpower was humiliated by a rag-tag peasant army in Vietnam.

The Vietnamese resistance took over cities all over South Vietnam in the Tet offensive, showing that the US could be defeated. Anti-war activists were vindicated. Workers and students the world over took heart that even the mightiest regimes could be beaten.

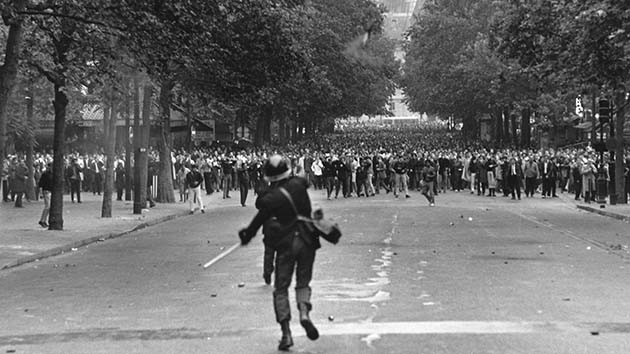

Then in May ten million French workers went out on general strike, responding to police brutality against student protests. Street fighting and factory occupations rocked one of the world’s richest countries. Grievances amongst workers had piled up over many years. And the student revolt was like a spark to this flammable tinder.

Student protests, begun over campus issues, soon spread into occupations over lack of proper services and a wholesale critique of capitalist society. When the police attacked them, and workers rushed to their aid, the stage was set for a mighty confrontation.

Although the union bureaucracy was eventually able to wind down the strike by channelling people’s fury into the ballot box, May 1968 saw the birth of the radical student movement in France and many revolutionary organisations grew out of it. It also resulted in many significant gains for the French working class.

And it showed that revoltion was possible even in the rich capitalist countries.

Build up

The decades before 1968 were marked by a conformist calm in the rich countries of the West.

Capitalism was going through the most sustained expansion ever witnessed and the system appeared to have solved its in-built tendency towards crisis. Unemployment fell. The welfare state was built and working class living standards steadily rose. Centre-left and centre-right political parties were converging in terms of policy and ideology.

It seemed like class conflict was over and that workers’ and bosses’ interests were actually aligned. Some said workers in the West had been “bought off”, and were too affluent and conformist to rise up against the system. The year 1968 proved them wrong.

New student movements began to develop first. In 1964 Berkeley in the US exploded with thousands of students demonstrating and occupying buildings, demanding freedom of speech on campus. Italy, Germany, Britain and Spain all followed suit, with thousands of students becoming radicals and seeking out revolutionary ideas.

The conditions for this outbreak of revolt had been prepared by the expansion of the education system. Before the 1960s, students were mostly members of the ruling class. But the needs of capitalism had seen universities opened up to more middle class and working class people.

The university presented an ideal of unlimited intellectual development, free from social, political and ideological restraint. However, students soon learnt that those who ran the universities did not practice what they preached.

Far from being liberal and democratic, the universities were firmly under the control of representatives of the ruling class, who would react to any challenge with expulsions, the police and the courts.

The university authorities would claim to be “non-political”, yet would collaborate with government war efforts and tolerate racism.

This meant that student protests which started off over liberal issues developed into all out confrontation. Later, students also connected with counter-cultural movements that were challenging the dominant socially conservative values.

Huge numbers of people were radicalised and believed revolutionary change was possible.

Yet the student movements had soon peaked. Students for a Democratic Society in the US went from 100,000 members in 1968 to completely dissolving itself by 1969. It was only where student revolt linked up with working class struggle that profound change became possible and revolutionary organisations continued to exist after the wave of revolt had receded.

Anti-war

One issue at the centre of the radicalisation was the Vietnam War. The decade leading into 1968 had seen the spread of national liberation movements throughout Africa, Asia and Latin America. The Vietnamese had been waging a 20-year anti-imperialist struggle against first French, and then US aggression.

The US government justified the war to its citizens using Cold War rhetoric, claiming it was protecting democratic South Vietnam from the communists in the North. But the South Vietnamese regime was a dictatorship that relied on US troops to survive.

From the very beginning, there were small numbers of US conscientious objectors who refused to go and fight despite being conscripted. Large anti-war protests began in the US from 1965. In Australia too, there was opposition emerging to conscription and the war itself.

As the war dragged on, it became clearer that the people who the US and Australian troops had been sent to “protect”, did not in fact want them there. This sapped morale in the invading armies. Many returned soldiers denounced their involvement, joining with anti-war activists and students to protest the war.

Black workers in particular began to identify with the oppressed Vietnamese as the growing US civil rights movement challenged the racial oppression they suffered at home.

Muhammad Ali refused to be drafted and famously defended his decision: “No Viet Cong ever called me nigger”.

The Vietnamese Tet Offensive in 1968 deepened all of these currents. Up until this point, the Vietnamese forces in the National Liberation Front (NLF) had waged guerrilla warfare through hit and run tactics, mostly in their rural strongholds. For the first time they attacked US positions openly, hitting major cities including Saigon. This shattered the US government’s lies that it was winning the war.

It was a shot in the arm for anti-war activists and unionists in the West. In March US President Lyndon Johnson announced he would not re-contest the presidential election. The revolt against the war had helped destroy his presidency.

By 1970 in Australia unions were taking strike action against the war as part of the Moratorium marches under the slogan of “Stop Work to Stop the War”. In Victoria the grouping of 27 “rebel unions” called for Australian soldiers to mutiny.

This was vital for linking the imperialist ambitions of the Australian ruling class with the exploitation they meted out to workers at home and also emphasising that it was workers’ power that held the key to ending the bloodshed. It showed the possibilities for turning the student and anti-war rebellion into a rebellion against capitalism.

Stalinism

The state capitalist regimes of the USSR and Eastern Bloc were not immune from revolt either. In reality the USSR and the Eastern Bloc regimes had nothing to do with socialism. They were societies controlled by a bureaucratic elite, using the state to exploit workers just as viciously as private capitalists exploited workers in the West.

The pro-Moscow communist parties in the West idolised these countries and held them up as a model of socialism. But the reality was that they were repressive capitalist regimes, driven by military competition with the West. This forced them into squeezing their workers and this provoked uprisings to improve living conditions.

The 1968 Prague Spring was born of this pressure. A faction fight in the communist party of Czechoslovakia led to mass agitation campaigns amongst the people. Suddenly students were organising assemblies to debate questions, people were buying and reading all sorts of papers and workers began to oust officials from state-run unions.

This sort of political activity had been brutally repressed for decades. Moscow demanded the regime clamp down and restore “normality”. But the regime’s leaders were paralysed by the struggle from below.

So Russia invaded with thousands of tanks, taking over major cities and killing hundreds of civilians.

Students occupied universities with the support of sections of workers. But ultimately, the radicals leading the resistance were not ready for a confrontation that would lead to revolution and Moscow was able to reimpose bureaucratic control. Still, the protests revealed to many people that the socialism of the “socialist world” was as phoney as the freedom of the “free world”.

The leaders of the Western Communist Parties found it increasingly hard to write off these protests and applaud the Russian tanks, as they had done with the Hungarian revolution in 1956. Some of them issued statements protesting against the invasion of Czechoslovakia. Other Stalinist parties split over the question. It marked the point from which many Stalinist parties around the world entered into a terminal decline.

Importantly, the layers of newly radicalised activists now took revolutionary inspiration in the possibility of socialism from below and no longer felt the need to support Moscow.

In the decades following 1968 the ruling class around the world fought back viciously.

Workers suffered a series of devastating defeats in the 1980s at the hands of neo-liberal leaders such as Thatcher and Reagan, whose effects still cast a shadow on our times. But the turbulent revolts of 1968 provide inspiration that another world is possible, one based on human needs and driven by movements from below.