The Wobblies combined opposition to the First World War with militant industrial organising, but their intransigence was also their undoing, argues Lachlan Marshall

Not a lot is remembered about the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) a century after the peak of their influence during the First World War. Yet as Australia is once again at war it is appropriate to examine the politics and practice of the most principled and energetic opponents of that bloodbath.

The IWW, known colloquially as the Wobblies, consistently argued for militant forms of direct action like strikes and sabotage against employers to win better wages and shorter working hours.

They emphasised building struggles from below and reserved their harshest criticism for the parliamentarism of the Labor Party. As Vere Gordon Childe claimed, the IWW was “the first body to offer effectively to the Australian workers an ideal of emancipation alternative to the somewhat threadbare Fabianism of the Labour Party.”

Moreover, they stood for anti-racism, internationalism and equal pay for women at a time when other organisations of the working class, like the Labor Party and most trade unions, clung to reactionary ideals like the White Australia Policy.

These principles stemmed from the IWW’s emphasis on organising workers at the point of production, which meant that overcoming racial and other divisions were of the highest priority.

But they saw politics, which they equated with parliamentary action, as a distraction from the industrial struggle.

At its height in early 1917 IWW membership stood at 2000. The Wobblies’ paper, Direct Action, had a circulation of 15,000 copies, although its readership would have been much larger.

However the IWW’s life as an organisation was short lived. Their attempt to combine a revolutionary organisation and a trade union in the one body meant they ultimately failed at both tasks.

Syndicalism

The IWW stood in the tradition of syndicalism, an influential current in the US and European labour movements during the period of intense working class struggle around WWI. (The peak of Spanish syndicalism was reached during the Civil War of the 1930s).

While syndicalist theory and practice varied, they converged around rejection of parliamentary politics, political parties and the state; insistence on trade unions as tools of revolutionary action; and an emphasis on direct action culminating in the revolutionary general strike to overthrow capitalism and usher in a socialist society of workers’ control and industrial democracy.

There is a tension in the syndicalist tradition over whether to organise within existing unions—“boring from within”—or set up separate revolutionary unions—“dual unionism.”

The American IWW, the inspiration for the Australian Wobblies, tended to opt for “dual unionism,” organising the unskilled, migrant and black workers excluded from the mainstream labour movement and the conservative American Federation of Labor.

On the other hand, the relative strength and organisation of the Australian labour movement—encompassing skilled and unskilled workers—made such a strategy unrealistic. On the whole the Australian Wobblies were forced to “bore from within.”

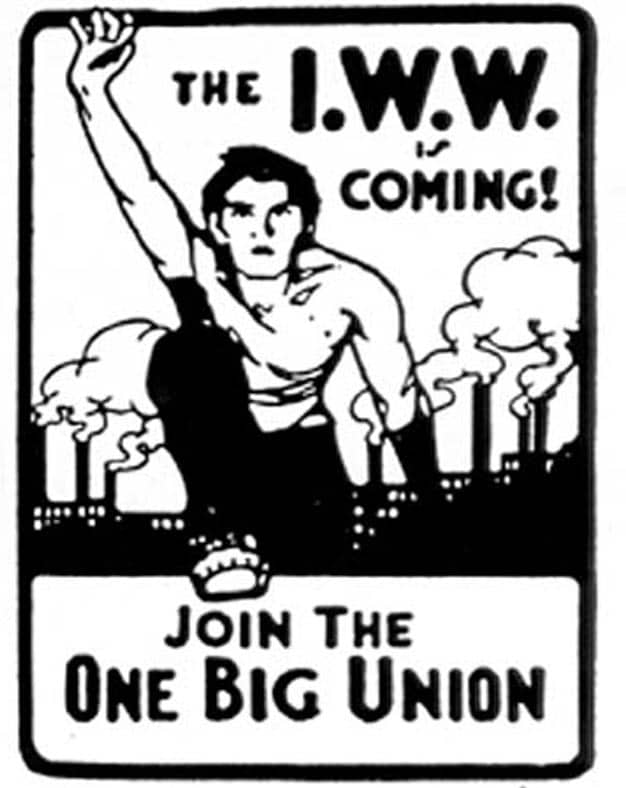

Nevertheless, the IWW’s goal remained the replacement of the existing unions by new “industrial unions” and the formation of One Big Union that would unite the entire working class.

The Australian Wobblies

The origins of the Australian IWW as a national organisation lay in the IWW Clubs, formed in 1907 by the Socialist Labour Party in Sydney, Melbourne and some NSW mining towns.

Echoing debates in America between the Chicago (non-political) and Detroit (political) factions of the IWW, Chicago-aligned direct actionist IWW Locals in Adelaide and Sydney coalesced in 1911 and eclipsed the Detroit-oriented IWW Clubs. By November 1913 the IWW had 199 members.

A number of factors explain the rise of the Australian IWW.

Firstly, the early years of the 20th century saw a massive growth of the organised working class. Between 1901 and 1909 the number of unions doubled while union membership trebled.

However, this was accompanied by the consolidation of a conservative layer of union officials. The Commonwealth system of Arbitration introduced in 1904 exacerbated this, shifting the focus from the shop floor to arbitration courts, and strengthening the hand of the union bureaucrats who represented their members in court.

Finally, the disappointing experience of the first federal Labor government from 1910, and earlier State Labor governments, gave weight to the IWW argument that parliamentary politics was a sham.

As Prime Minister Hughes acknowledged in federal parliament in 1917, the IWW’s popularity represented “the revolt of the people against the chicanery of legislatures.”

WWI and conscription—the high point

The IWW shone brightest in its opposition to the war and conscription, which led to growing influence in the unions as workers began to suffer from inflation caused by the war.

The IWW opposed the war from the beginning. It denounced the betrayal of the socialist parties of the Second International, correctly attributing their capitulation to the aim of taking over the state through winning control of parliament which, “lead the Socialist parties to the defence of the national state…”

In 1916 the Wobblies led strikes in the shearing and mining industries to victory, often coming to the assistance of workers who had been abandoned by their own unions.

In Northern NSW and Queensland shearers wanted a pay rise to match the booming profits enjoyed by the pastoralists. In August 1916 they went on strike in defiance of their union, the AWU, which planned to wait for the old agreement to expire. So the shearers appealed to the IWW for assistance instead.

The IWW seized the opportunity and despatched an organiser to assist the strike. It helped sustain the strike through collections from its Locals and in the Sydney Domain, and its newspaper, Direct Action reported on the strike’s progress. They printed thousands of stickers that read: “Don’t scab on the Shearers – Let the Blowflies win the Strike.”

With the pastoralists terrified of losing the whole season’s wool clip as sheep began dying from fly-blow, they eventually conceded the shearers’ demands. It was a vindication of the Wobbly tactics of bypassing arbitration and insisting on direct action.

The next major strike involving Wobblies was by NSW miners in November 1916 for a pay increase and reduction in hours, which was joined by miners in Queensland, Victoria and Tasmania.

The press howled that the IWW were working for the Germans. But with the nation heavily reliant on coal to fuel the war-time economy, the strike forced the intervention of Prime Minister Hughes to instruct the arbitration tribunal to grant the workers’ demands.

Even where there were no IWW members Wobbly influence was evident. For example, in the lead-up to strikes at the NSW railway workshops in Randwick in February and Eveleigh in April 1916, where workers acted independently of their leaders, Wobblies had held lunch-time meetings at the factory gates and put posters up around the workshops.

Similarly, the NSW general strike of 1917 bore the hallmarks of IWW influence, with workers walking out against the opposition of their union officials.

But it was the anti-conscription campaign that gave the IWW its greatest opportunity for growth. Throughout the campaign the IWW displayed a feverish level of activity, spreading its anti-war propaganda in hundreds of IWW meetings.

In July 1915 the IWW and other socialists launched the Anti-Conscription League, a campaign in which they collaborated with the left of the Labor Party.

Hughes resorted to a referendum rather than legislating to introduce conscription because even the Labor Party caucus wouldn’t pass a Conscription Act.

Hughes, albeit with some exaggeration, blamed the IWW as “largely responsible for the present attitude of organised labour, industrially and politically, towards the war.”

Importantly, the IWW put its anti-racism to the fore in the campaign, arguing against those who warned of the “threat” coloured labour would be imported to replace workers conscripted to the front.

Following his defeat in the first conscription referendum, Hughes split from the Labor Party and established a new “National Labor” Party. He failed again in a second conscription referendum in December 1917.

Fall of the IWW

From a peak in July 1915 military recruitment fell steadily, leading to increased government repression of opponents of the war effort—in particular the IWW.

In September 1915 Wobbly agitator Tom Barker was charged under the War Precautions Act for publishing a poster “prejudicial to recruiting,” and then jailed in March 1916. He was released in August after an impressive defence campaign. But the government was only biding its time.

The following year Hughes told a meeting of union leaders that the IWW must be repressed “with the ferocity of a Bengal tiger.”

In September 1916 the IWW hall in Sydney was raided. Membership lists confiscated were passed on to employers, who dismissed IWW members en masse.

The following month twelve leading IWW activists were arrested and charged with treason, receiving sentences of between ten and 15 years.

A campaign to “set the twelve men free” attracted wide support, including from unions hostile to the IWW and even the Labor Party. It was so blatantly a frame-up that even those who shared none of the Wobblies’ convictions demanded a new trial. It later emerged that police simply fabricated evidence to secure convictions.

At Broken Hill, a bastion of Wobbly influence, miners called a general strike for the release of the Twelve, with some going so far as to take possession of the mines in December 1917, until local authorities were reinforced by South Australian police.

Most of the Twelve were freed within a few years. But the damage to the IWW had been done.

The passage of the draconian Unlawful Associations Act in December 1916, which had the explicit aim of muzzling the IWW, resulted in sackings, the jailing of over 100 members, and deportation of foreign-born members (who comprised a large part of its leadership). The organisation lay in tatters.

Revolutionary?

Unlike anarchism with its complete rejection of authority and fetishisation of individual freedom, syndicalism stressed unity, organisation and discipline against the capitalist class.

However, the IWW still had a tendency to celebrate individual, “heroic” acts of resistance that could lead to easy isolation and repression by the state. These included acts of sabotage and even the counterfeiting of banknotes in the belief that this would hasten the downfall of capitalism. Such acts provided a pretext for the arrest of leading Wobblies and were very hard to defend with collective workers action.

When the state crackdown came they also failed to avoid confrontations they had no chance of winning, or to prepare to operate illegally.

Some IWW branches, with typical bravado, simply vowed to “retaliate by filling the jails.”

Tom Barker explained their myopia: “We didn’t go into hiding. I don’t think we ever thought much about what we should do if we were declared illegal. We expected it to come and we just waited until it did come and then carried on despite it.”

This underestimated the severity of the state’s attack, which called for an orderly retreat and reorganisation, not ultra-left posturing.

However, the more fundamental contradiction of syndicalism lay in its aspiration to function simultaneously as a trade union and a revolutionary organisation.

In order to gain sufficient bargaining power within a workplace trade unions must recruit both militant and more conservative workers.

This meant the Australian IWW, with its uncompromising militancy, failed in its bid to build separate industrial unions. Most Wobblies were members of mainstream unions. The closest they came to dual unionism was in the Broken Hill mines, where the Amalgamated Miners’ Association (AMA) initially recognised the IWW membership card.

However this ended after the IWW declared itself a “Local Industrial Union” in July 1916 in an attempt to replace the AMA. The IWW tried to poach AMA members by undercutting it with low dues of only 10 cents per month, but their effort failed.

The revolutionary party

The Russian revolutionaries Trotsky and Lenin enthused about the prospects of collaboration with the IWW. On hearing that some former Wobblies had joined the fledgling Communist Party of Australia Trotsky commented, “That is good because the I.W.W. are the real proletariat and real fighters.”

But they also realised that to successfully lead a socialist revolution the minority of revolutionary workers had to be organised into a separate revolutionary party to lead the working class on both economic and political planes.

The IWW’s rejection of politics on the basis that it would sow unnecessary divisions and thus threaten industrial unity led to serious limitations.

For instance, while the IWW welcomed all women workers and supported equal pay, not many women could become Wobblies because membership required that they be wage-labourers, a status often restricted to women at the time.

And economic struggle, once it reaches a certain stage, inevitably confronts the question of political power.

Syndicalism’s belief that power would pass into the hands of the working class as an automatic outcome of growing economic unity, summed up in Direct Action as, “First, education; second, organisation; and finally, emancipation,” passed over the fact of unevenness of consciousness within the working class and the need to engage in a protracted battle of ideas to win over the majority to revolutionary politics.

In a debate with British syndicalist Jack Tanner at the Second Congress of the Comintern in 1920, Lenin responded:

“If Comrade Tanner says he is against the Party but in favour of a revolutionary minority of the most determined and class-conscious proletarians leading the whole proletariat, then I say that in reality there is no difference between our points of view. What is the organised minority? If this minority is really class-conscious and able to lead the masses and give an answer to every question that stands on the agenda, then it is actually the Party.

“If comrades like Comrade Tanner, who are particularly important for us because they represent a mass movement … want a minority that will fight with determination for the [proletarian] dictatorship and educate the mass of workers along these lines, then what they want is a party.”

Under the leadership of the Bolsheviks in 1917 the Russian working class not only overthrew capitalism but took power into their own hands, through the soviets, or workers’ councils.

The emergence of workers’ councils in Russia and elsewhere in the wake of the Russian revolution was seen by many syndicalists as the embodiment of the syndicalist ideal of workers’ control and industrial democracy, and led to many joining the burgeoning Communist Parties.

The Wobblies were pioneering propagators of an anti-racist, anti-war and revolutionary current in the Australian working class. Their frenetic activity and tireless agitation aimed at building socialism from below, militant strike leadership and successful anti-conscription campaigning continue to be a source of inspiration for revolutionary socialists today..

However, the crushing of the IWW shows the extreme lengths the state will go to defend the power and privilege of the capitalist class. This pressure exposed some of the fundamental limitations of their syndicalist strategy that unnecessarily isolated them. And revolutionary workers can not stand aloof from politics, there is an imperative to organise the most militant and class-conscious sections in a revolutionary party that can meet the challenges of changing circumstances and chart a path forward for the struggles of all workers and the oppressed.

Further Reading:

Revolutionary Industrial Unionism: The Industrial Workers of the World in Australia by Verity Burgmann;

Radical Unionism: The Rise and Fall of Revolutionary Syndicalism by Ralph Darlington