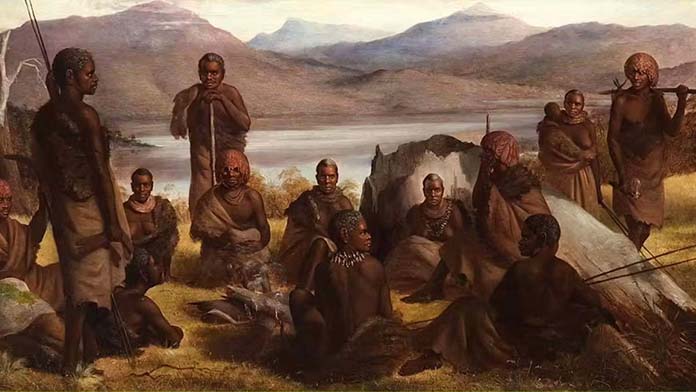

Cassandra Pybus’s book, Truganini, highlights the damning treatment and decimation of First Nations in lutruwita—now known as Tasmania.

Truganini details the early years of colonisation and the lies and broken promises made to the original owners—including the book’s namesake, Truganini.

It is also a withering expose of the role of George Augustus Robinson, a self-styled missionary from Scotland, in the attempt to remove all Indigenous people from mainland Tasmania.

Robinson arrived in Tasmania in 1824, establishing a construction business. But as guerrilla warfare grew, the Governor of Van Diemen’s Land, George Arthur, declared martial law in November 1828. In March 1829, Robinson was appointed to make contact with the Indigenous clans of Tasmania.

His principal task was to persuade them to move to the “asylum” of Wybalenna on remote Flinders Island in Bass Strait.

To gain some protection from martial law, Truganini, a Nuenonne woman from Bruny Island, became one of Robinson’s crucial guides and facilitated his contact with the various tribes around Tasmania.

As the desire of the colonial authorities to rid mainland Tasmania of its First Peoples grew, Robinson’s compassionate motivations also became more questionable as he resorted to threats of violence, lies, and deceit. Robinson’s shocking racism permeates the book.

Robinson made promises to Indigenous leaders like Mannalargenna of the Trawlwoolway and Umarrah of the Tyerrernotepanner that if they went to Flinders Island and stopped attacking settlers, they would ultimately be returned to enjoy their traditional country. His promise was never fulfilled. Both Mannalargenna and Umarrah and many of their people died away from their Country.

In 1833 Robinson had come to the realisation during an expedition to remove west coast First Nations people that “if their children were taken away from them they would probably die of grief”.

Yet just days before he wrote this, he had sent a child away from her parents to Hobart, where she would never see them again.

Despite Robinson’s formal objections to the authorities, child removal was a feature of the Wybalenna mission. Nine children were sent from Wybalenna to Hobart’s orphan school in February 1835 to take them away from the “heathen lifestyle of their parents” and Christianise them.

But in the measles outbreak in Hobart a few months later, half the children died and the survivors were sent back to Wybalenna.

At Wybalenna, Robinson also systematically collected skulls by decapitating corpses and boiling down the flesh, sending two skulls to the then Governor’s wife, Lady Jane Franklin.

In 1839, Robinson also sent two children to Lady Franklin, despite one of the children’s mothers still being alive, dutifully fulfilling Franklin’s request for Robinson “to get a black boy for her”.

Wybalenna operated for 15 years (1833-47). Four-fifths of the Indigenous people sent there died.

Genocidal mission

By 1835 Robinson could claim that he had achieved his mission of ridding mainland Tasmania of its First People. He was rewarded with a substantial land grant (which he sold for a tidy profit) and a lifetime pension of 200 pounds a year. His sons were granted plots of land of 1000 acres and 500 acres.

In 1835 the infamous settler, John Batman, known for leading massacres in Tasmania and abducting Aboriginal women and boys, sailed to Port Philip in mainland Australia and negotiated a “treaty” with people of the Kulin nation.

This “treaty” involved trading items such as blankets, knives, and flour in return for using 6000 acres of Kulin land in perpetuity as the “real proprietor”.

Alarmed that he had taken land without colonial authority, the British government declared the treaty had no legal standing.

Robinson saw an opportunity to escape the self-acknowledged disaster of Wybalenna and continue his “civilising” mission by taking Tasmanian First Nations to Port Philip. But Indigenous tribes around the new colonial settlement of what is now Melbourne endured a similar fate to First Nations in Tasmania—invasion, resistance, disease and death.

Truganini is a valuable addition to the shocking history of the origins of Australia. As Pybus puts it, “The expropriation of … a generous people and the devastating frontier war and the dispersal that followed, is Australia’s true foundation story.”

First Nations’ resistance challenged colonial control over the newly claimed territory and impeded their ability to exploit the land for domestic and international markets.

Truganini ends with a plea for a treaty (Makarrata) and a Voice to Parliament. But the story Pybus has written surely demonstrates that racism and the legacy of dispossession are too deeply embedded in Australian capitalism to be eradicated by a few lines in the constitution.

By Luke Ottavi

Truganini: Journey through the Apocalypse

By Cassanda Pybus

Allen and Unwin, $34.99