On 6 October, a joint statement by the PNG and Australian governments announced that PNG would “assume full management of regional processing services … and full responsibility for those who remain”.

It was the latest move by the Australian government to use PNG as a dumping ground for the asylum seekers it first sent to the horror of Manus Island detention centre in 2013.

The declaration gives the 124 refugees and asylum-seekers who remain in PNG the “choice” of settling in PNG or transferring to Nauru before 31 December 2021. (Although the option of transfer to Nauru is not open to refugees with PNG families.)

But the choice is no choice at all. Australia signed an agreement with Nauru on 24 September to maintain offshore detention there indefinitely.

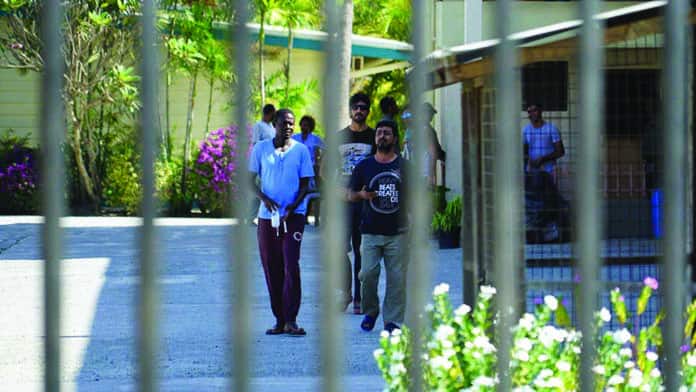

As for PNG, it remains unsafe for refugees and incapable of providing enduring security. Assaults and robberies of refugees are still common; a reality which has rendered refugees prisoners in their scattered accommodation in Port Moresby hotels.

Although the agreement says that refugees will be entitled to citizenship and family reunion, the conditions are not spelled out.

In any case, PNG is also incapable of providing the education and employment that refugees and their families need. Despite signing the Refugee Convention in 1986, PNG has never agreed to resettle refugees.

As the UNHCR politely put it, “The systems needed for long-term successful local integration in PNG are still undeveloped and largely absent.”

Given the precarious existence of refugees who have been living in Port Moresby for the last two years, no one has any confidence that the agreement is worth the paper it is written on.

Ironically, the agreement highlights the precarious existence of refugees from Manus and Nauru who are still being held in detention in Australia or are subsisting in the community, denied any security, on bridging visas.

The agreement would seem to put the final nail in the coffin of PNG ever being used as an offshore destination for people seeking asylum in Australia, yet leaves so much unfinished business.

Those refugees transferred from PNG to Australia under the Medevac legislation but still being held in detention, must be freed.

The decision also has potential implications for any deal with New Zealand. With Australia formally severing its control over the refugees, it will be open to New Zealand to directly accept refugees from PNG. But any deal between Australia and New Zealand will only refer to refugees held on Nauru.

In limbo in Australia

In 2013, then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd declared that no one sent to Manus or Nauru would ever be resettled in Australia; a declaration made repeatedly since then by Liberal Prime Ministers.

But there are hundreds of refugees from PNG living in the Australian community on precarious bridging visas. It was already clear that those refugees (and hundreds of others from Nauru) have effectively been resettled in Australia.

The declaration makes it even clearer that they will not be going back to PNG.

Yet they are being deprived of permanent visas (and the right to family reunion, education and travel that goes with them) and the resettlement income and accommodation support that would normally be available.

Despite the declaration, the torture of those sent offshore hasn’t ended. And, shamefully, Labor remains committed to offshore detention, with Labor’s Home Affairs spokesperson, Kristina Keneally, repeating that, “Offshore processing was an important part of Operation Sovereign Borders”.

Labor’s commitment to Operation Sovereign Borders also means that while it will grant permanent visas to all those refugees on temporary protection visas, it has refused to offer permanent visas to those refugees from PNG and Nauru living in Australia on bridging visas.

We need to get rid of Scott Morrison and the Liberal government but it will take more than electing Labor to end offshore detention.

To end Operation Sovereign Borders, the refugee movement will need to keep up the protests and its demands to bring those still on PNG and Nauru to Australia; to free all those being held in detention in Australia; and grant permanent visas to all.

By Ian Rintoul