This year 19 July marks the beginning of the ninth year of Offshore Detention Mark II.

Eight years ago, then Labor Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd, announced on 19 July 2013 that asylum seekers arriving by boat would be sent to Nauru or Manus Island, and none would ever be settled in Australia.

Eight years later, there are around 233 asylum seekers and refugees still held in PNG and Nauru. And 100 more (including the refugees brought under the Medevac legislation in 2019) are still being held in detention centres and hotels in Australia.

Rudd’s announcement opened one of the darkest chapters in Australia’s shameful history of immigration detention. The Liberals went further when they were elected in September 2013 (with Tony Abbott as Prime Minister and Scott Morrison as Immigration Minister). They called in the military to command Operation Sovereign Borders and added boat interceptions and turnbacks to the war against refugees.

In a recent report, the UN special rapporteur on the human rights of migrants estimated that Australia has turned back 800 asylum seekers on 38 boats since 2013, but few have ever been reported because of the government’s policy of strict secrecy regarding “on water matters.” In 2018, the UN working group on arbitrary detention condemned Australia’s indefinite incarceration of refugees and asylum seekers, while previous reports accused Australia of violating the Convention Against Torture for holding asylum seekers in dangerous and violent conditions on Manus Island.

But the Australian Solution is spreading globally. In early June, Denmark passed a law enabling it to process asylum seekers outside Europe, having signed a memorandum of understanding with Rwanda, which is already housing refugees relocated from Libya.

Shortly after, Britain indicated its interest in teaming up with Denmark to establish a shared refugee processing centre in Rwanda. And now, Britain’s home secretary, Priti Patel, has introduced a Nationality and Borders Bill (previously known as the Sovereign Borders Bill) that mirrors the suite of Australia’s anti-refugee policies.

The new laws will expand detention centres, provide for the removal of asylum seekers to offshore processing centres, establish prison sentences for illegal entry (read boat arrivals), and make it easier to remove asylum seekers who arrive in Britain unlawfully.

Patel is also taking her talking points from Tony Abbott, declaring the new laws will allow, “the British people…to take full control of its borders… crack down on vile, criminal smugglers who bring asylum seekers across the Channel, and break the business model of criminal trafficking and save lives”.

The fight to end offshore detention has grown more urgent.

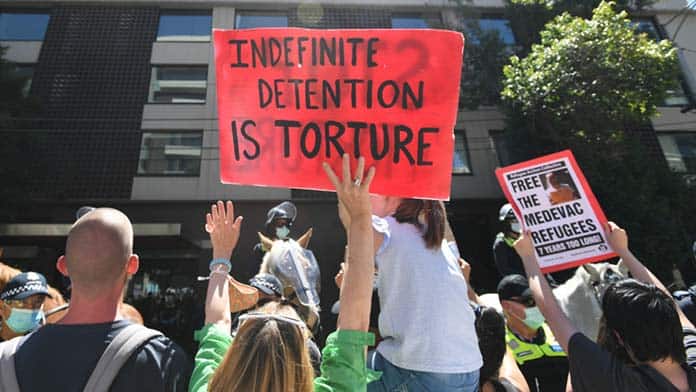

That fight, for the moment, is focused on the Medevac refugees still in detention in Australia. They need their freedom—they need permanent visas. But the dark chapter that opened in 2013 won’t be over until all the asylum seekers and refugees brought from Nauru and PNG and living in community detention or on bridging visas become permanent residents, those remaining in PNG and Nauru are brought to Australia (or safely resettled), and Nauru is finally closed.

Medevac refugees start hunger strike

As Solidarity goes to press, around 12 Medevac refugees have re-started their hunger strike protest in the Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation (MITA).

The 12 were all part of the group of 14 refugees who staged a hunger strike in MITA in late June. Although that hunger strike ended on 3 July, one refugee is still not well enough to leave Northern hospital. 19 July will mark the beginning of their ninth year in detention too.

“We are very tired,” one of the hunger strikers told Solidarity, “Next Monday [19 July], we are nine years in detention. No-one can tell us why. Since our last hunger strike, we did not get any answers.”

In late June, the High Court decision in ALJ20 put the possibility of legal action freeing the Medevac refugees further out of reach. The decision found that even if the government was not holding them for the “temporary purpose” of their transfer (ie they are not getting their needed medical treatment) or making any arrangements for their removal, their on-going, indefinite detention was lawful.

Protests are continuing at Brisbane’s detention centre (BITA) where over 30 Medevac refugees are being held, outside Darwin detention, outside MITA, and outside the Park Hotel in Melbourne.

By Ian Rintoul