The Australian Labor Party’s leaders have backed Israel from the beginning, playing a key role in the UN partition plan in 1947 that triggered the Nakba, writes Tom Orsag

Anthony Albanese’s support for Israel’s atrocities against Palestinians in Gaza is not an aberration. In August 2023, Labor leaders blocked a vote at the party’s national conference on Australian recognition of Palestine.

But the Labor tradition of supporting Zionism dates back much further, to the birth of Israel in 1947-48.

The ALP has supported Zionism despite the party’s sordid history of antisemitism.

And its support has little to do with economic links. In 2019-20, Israel was only Australia’s 45th largest two-way trading partner and only the 50th largest export market at about $1.3 billion.

Instead support for Israel has always been a strategic question, with the Australian ruling class looking to the dominant imperialist power of the day—first Britain and, over time, the US—as a guarantor of Australian domination of its own region.

In 1947, Australia was still connected to British imperialism. Oil and shipping routes were part of the British interest in the Middle East.

According to biographer Ken Buckley, these were “major points of consideration in ensuring Australian support for Britain during the [United Nations] Assembly debate over the UN Sub Committee on Palestine report”.

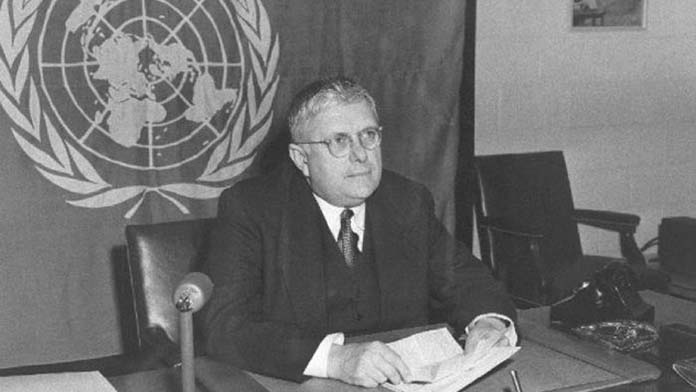

Herbert V. Evatt, Labor External Affairs Minister from 1941 to 1949 and future ALP Opposition leader, was instrumental in the UN partition of the British Mandate of Palestine as chair of its Ad Hoc Committee on the Palestinian Question and then in his role as President of the UN in 1948-49.

Australia’s support for the partition of Palestine and its recognition of Israel during the height of the Zionists’ ethnic cleansing of Palestine, known in Arabic as the Nakba, was due, in part, to Evatt’s desire to maintain the British Empire, which he saw as central to Australia’s interests.

Australia had turned to the US for military support in December 1941. But once the Second World War was over in 1945, Australia looked once again to Britain for its defence needs, while still encouraging the US to stay in the South Pacific.

Labor’s wartime Prime Ministers, John Curtin and Ben Chifley, were, as author Gideon Haigh put it, “invested in the [British] empire’s continuity”.

In late 1944, Evatt told the US Ambassador to Australia, Nelson T Johnson, that, “The Commonwealth Government did not want to do anything that would lend colour to the belief that it was trying to part company with the Empire.”

Another biographer, Peter Crockett, wrote, “Evatt aimed for a comprehensive post-war arrangement involving the US and other powers, but principally Britain and New Zealand, to protect the region.”

Evatt also wanted Australia to join the table of the Big Four Powers—the US, Russia, Britain and China—in planning war strategy and the shape of the post-war world.

He argued that by the war’s end Australia’s “successful war effort will have converted Australia into a great nation”. He added: “We cannot escape such a destiny. In truth, we will be trustees not only for British civilization, but also for a decent world order in the Pacific sphere of influence.”

Evatt was a former NSW MLA and High Court judge who had visited Britain and had been appointed to its Privy Council. He was fully integrated into the British world view of imperial pre-eminence, racism towards Arabs and the Balfour declaration of 1917 of a “Jewish homeland” in Palestine.

Bankruptcy

Britain had held a Mandate to control Palestine since the end of the First World War.

It had encouraged Zionist migration to Palestine, but when the Second World War ended it was clear Britain was in decline as an imperialist power, and the Zionists felt strong enough to push for their own state.

In July 1946, the Zionist terrorist militia, the Irgun, blew up the King David Hotel in Jerusalem which housed the offices of the British Mandate, killing more than 90 British, Arabs and Jews.

The Zionists’ murderous action exposed the bankruptcy of British policy in the Mandate and the British hurriedly passed the fate of the territory back to the UN.

Buckley writes, “In fact Evatt intervened in the issue only when the British made it clear that the Mandate was becoming an acute embarrassment to them.”

Evatt favoured the partition of Palestine not only because it would allow Britain to save face but because he wanted to protect Australia’s racist laws from UN interference.

If Palestine became a unified majority-Arab state, it could, under UN rules, be forced to admit more Jewish immigrants on the grounds of non-discrimination.

This precedent could then be applied to the White Australia policy.

As the Australian delegation to the UN saw it, it could lead to “the UN attempting to open the doors to Australia to Asiatic immigration … and that Australian immigration policy was contrary to the principles of the [UN] Charter in so far as it involved racial discrimination”.

For Evatt, Palestine had to be partitioned so that Jewish-only immigration to their own state would not contravene UN principles.

Haigh wrote, “No task so consumed Evatt’s energies as the division of Palestine.” Author John Murphy noted, “The Americans proposed a renewal of the trusteeship [to Britain] … but Evatt remained actively committed to partition.” Murphy added, “His stance had little to do with the Holocaust.”

Antisemitism

Support for Israel’s establishment went hand in hand with antisemitism in Australia. There was a long history of antisemitism inside the Australian ruling class. As the Zionist historian, Suzanne Rutland, wrote in The Conversation in 2023, “Open antisemitism started to become prevalent in the 1880s with the emergence of Australian nationalism and the campaign for federation. It was further fuelled by fears of an influx of Jews fleeing the pogroms in Russia.”

The small numbers of Russian refugees were not welcomed by politicians, unions and the media. Popular publications like The Bulletin and The Truth voiced anti-Jewish racism as well as anti-Chinese racism.

Labor had long drawn from the deep well of Australian racism and conservatism fostered by the ruling class.

But as a capitalist workers’ party it chose to redirect working class hatred of capitalists in a racist direction via antisemitism.

In 1915, left-wing federal Victorian MP Frank Anstey re-published his series of anti-Jewish newspaper articles as a pamphlet called The Kingdom of Shylock as part of his opposition to World War One.

There were large waves of Jewish refugees worldwide before and after World War Two, including Holocaust survivors fleeing Europe.

In July 1942, a speaker from the Zionist World Jewish Congress who addressed the NSW Labor Council on the fate of European Jewry was “roundly heckled” with anti-Jewish capitalist slurs.

Before World War Two, there were fewer than 40,000 Jews in Australia.

The arrival in Australia of Jewish refugees after World War Two was met with an antisemitic outcry in the newspapers, as well as in statements by MPs.

Resolutions against Jewish migration were passed by Australian nationalist groups such as the forerunner of the Returned and Services League of Australia (RSL) and the white Australian Natives Association (ANA).

In 1946, in response to the anti-Jewish hysteria, ALP Minister for Immigration, Arthur Calwell, made administrative changes to ensure the Jewish community stayed a tiny minority of the population at 0.5 per cent.

His restrictions included a 25 per cent limit on Jewish passengers on ships bound for Australia, later extended to airplane arrivals.

Imperial rivalry

In using his role in the UN to try to cement Australia’s link with Britain in the post-war world, Evatt became the “nation-maker” of Israel.

As chair of the UN’s Ad Hoc Committee on the Palestinian question from September 1947, he ignored opposition to the UN Partition Plan and a proposal for a one-state solution from the Arab Higher Committee, the Palestinian leadership.

This meant the views of the overwhelming 70 per cent majority of Palestine’s population were simply disregarded.

Evatt’s Partition Plan in 1947 meant Israel was to have 55 per cent of the land, with 30 per cent of the population. Most of the Jewish population had only arrived in the previous 20 years as settlers with British support.

The countryside was still overwhelmingly Palestinian, with only 5.7 per cent of the land owned by Jewish settlers in 1947, and the bulk of the Jewish population living in the cities. This meant dividing the land into two states was bound to bring disaster.

The Zionists had already publicly announced their intention to expel and ethnically cleanse Palestinian Arabs to establish their state. But the UN plan made no effort to stop this.

By 1949, Israel’s military had seized 80 per cent of Palestine by war, terror and theft—none of which concerned Evatt.

As Zionist Daniel Mandel wrote, “Evatt’s preference for the Jewish cause put him in no moral quandary”, even when Israel carried out massacres of whole Palestinian villages, like Deir Yassin in April 1948.

Evatt’s loyalty was to Australian capitalism’s needs. Arab deaths mattered little in that equation.

He disliked Arab support for Germany and Italy in World War Two, which flowed from them being governed brutally by the British.

Following Palestine’s partition in November 1947, Evatt was elected as the fourth President of the UN General Assembly from July 1948 to June 1949.

The partition of Palestine was also supported by Russia and the “Communist” bloc, adding further confusion on the international Left.

Australia repeatedly submitted resolutions calling for Israel to be admitted as a UN member state. One such resolution failed in 1948. Another succeeded in 1949.

Australia formally recognised Israel on 27 January 1949, more than three months before the UN did so in May.

Unbroken

Since then, every federal Labor leader has been committed to Israel and the oppression of Palestinians.

The Australia Israel Labor Dialogue boasts of “an unbroken line” of Labor leaders supporting Israel—Chifley, Evatt, Calwell, Whitlam, Hayden, Hawke, Keating, Beazley, Crean, Gillard, Rudd, Shorten and Albanese.

Bob Hawke’s support for Israel was very public and very nauseating long before he became PM in 1983.

His position flowed from his backing of US imperialism (the US saw Hawke as an “asset”), especially after Israel defeated three Arab countries led by radical nationalists in the Six-Day War of 1967.

Egypt, Jordan and Syria threatened US interests in the region and were allied to Russia. Israel’s smashing victory over them made the US sit up and take notice.

During the early 1960s, US military loans to Israel averaged a paltry $A32 million a year, reflecting US disinterest in the country.

After 1967, US loans to Israel increased dramatically. Between 1970 and 1974, they rose to $A658 million a year.

The new-found usefulness of Israel to US imperialism meant Australia’s rulers had to take notice. Hawke, then president of the ACTU, visited Israel for the first time in July 1971.

By this time, the 1960s and 1970s wave of radicalisation, in particular opposition to the war in Vietnam, had created an audience for Palestine solidarity within the ALP.

The Victorian branch supported the Palestine Liberation Organisation and forced an “even-handedness” approach on Palestine on to federal Labor—positions Hawke fought against, especially as Labor President from 1973.

Labor’s support for Israel, due to its links to British and US imperialism, has put it on the wrong side of history ever since.

While individual MPs and branches may support Palestine, no MP aspiring to the leadership of the party can ever do so. Backing Israel is seen as a litmus test of loyalty to the Australian “national interest” and its imperialist allies.

Albanese’s journey from being an MP who spoke out for Palestine to being a prime minster supporting Israel’s genocide in Gaza fits the pattern perfectly.

All those who support the oppressed and, in particular, Indigenous people, stand with Palestine. Labor’s commitment to ruling for Australian capital means it will never do that.