After starting as an organiser in the militant BLF construction union, Kevin Cook went on to play a key role in Indigenous education and the fight for land rights, writes Niko Chlopicki

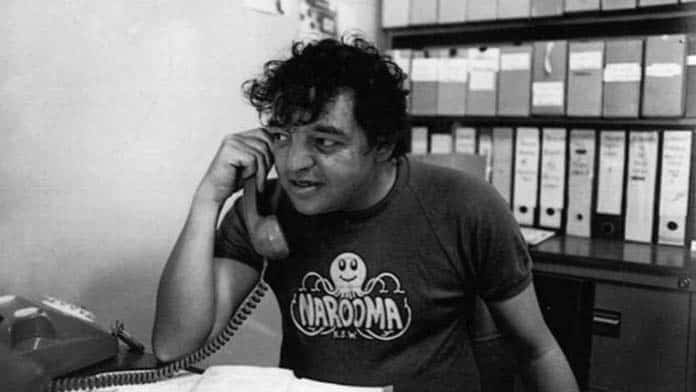

Kevin “Cookie” Cook was a proud Indigenous man, well known as a unionist in the Builders Labourers Federation (BLF) and as an Aboriginal activist and educator at Tranby College.

He was a key player in the fight for land rights and against Black deaths in custody in NSW.

When asked about what his life of activism had taught him, Cookie would talk about the importance of “sticking fat”.

To “stick fat” is to stick by those around you, through thick and thin, sharing not just the hopes but also the hard work involved. It is key to working together to make change.

Cookie was born in 1939 and raised in the shadow of the Port Kembla steel works in Wollongong. He was a descendant of the Wandandian people, who had close relations with the Yuin and Dharawal peoples, as well as among the working class migrant community.

After working in the steel mills in Wollongong, Cookie moved to Sydney to work in the construction industry.

Sydney in the 1960s and 1970s was undergoing a high rise boom. New construction techniques and materials allowed for bigger and higher buildings, yet this often meant dangerous conditions for workers. Initially there were no guarantees about permanent work, meaning workers were being treated as expendable and were forced to take risks with no safety protection.

Cookie worked as a dogman, responsible for riding the crane loads up to the towers with no safety harnesses or equipment. If you lost your balance you fell 20 storeys onto the footpath.

The literal life and death conditions created a deep sense of comradeship, where Cookie and others learnt the importance of working together and “sticking fat” to improve working conditions.

Being a dogman may have been a very dangerous job but also a very important one. As Cookie put it: “It was a job where you could do things. You had control of the crane. If you didn’t lift and didn’t put things where they wanted it to go, it’d hold up the job, and so you was a pretty important cog in the wheel.”

The new construction techniques also meant that workers, when organised, had more power than ever before. Cookie was part of the militant leadership that developed in the BLF around Jack Mundey, Bob Pringle and Joe Owens from the late 1960s.

Workers in the BLF would stop work at crucial moments in the building process to demand improvements in pay and conditions, including in the middle of concrete pours.

Originally, most of the disputes the union took on involved issues like basic safety and amenities, like fighting for a first aid officer on site, access to taps, suitable change rooms, workers’ compensation or defending workers who faced the sack.

Once these were successfully won, other problems didn’t seem so difficult to confront. BLF members gained a sense of their own collective strength and were able to translate that into struggle around wider social issues.

Eventually any issue that involved workers was suddenly the business of the BLF.

This period saw the anti-Vietnam and anti-Apartheid marches, issues of land rights for Aboriginal communities, equal pay for women, racist discrimination against migrant workers, and environmental activism—eventually leading to the famous BLF Green Bans.

The BLF in those days had a firm commitment to union democracy. BLF officials were often drawn from the most militant rank-and-file workers. Cookie himself became one in 1971.

Union officials within the BLF also did not serve for life but went back onto the job when their tenure was up.

This was in complete contrast to Cookie’s experience in the steel works at Wollongong where, as he recalls: “We were on strike for three days, and we called out the organiser—it took him three days to get out to us! And then he went to the boss first, come out to us and said, ‘Get back to work’.”

The decreased gap between the leadership and BLF members allowed for greater accountability.

In Cookie’s own words: “The union was very democratic. It showed a lot of people, especially me, what could be done by a very small amount of people if they all stuck fat. And those principles have carried on, all the way through to working with Aboriginal people in the early land rights campaign.”

Saving The Block

This intersection between Aboriginal rights and union struggle was perhaps most evident in the campaign to save “The Block” in Redfern.

The area had become a key centre for the Aboriginal population in Sydney, attracting many people who had left rural areas for better work and education opportunities in the city. But the pressure for development was displacing working class, low-income Aboriginal residents.

The demolition of The Block would not only have left residents homeless but would also have reduced access for Aboriginal people to low-cost housing in the inner city.

BLF members were supposed to be the ones to demolish the houses.

However, young Aboriginal activists who had been involved in stopping police from evicting tenants, called on the unions, particularly the BLF, to stop the demolitions, as they had already been involved in supporting Aboriginal movements and had sent members to attend demonstrations.

As a BLF organiser, Cookie worked directly with the Redfern community and helped to organise BLF members to ban any demolition work in The Block. He also worked to secure funding for the Aboriginal Housing Company (under local Aboriginal control) to purchase houses in The Block.

As liaison officer between the Aboriginal Housing Company and the BLF and other unions in the building industry, Cookie was able to use his union experience to assist Aboriginal workers.

The struggle for The Block is an important reminder of the advantages of “sticking fat” and forging connections between Aboriginal people and unionised workers. As Cookie argued: “We needed to take it out of the narrow focus of ‘these are issues for Aboriginal people and Aboriginal people need to be the ones that fight it’.

“These issues do restrict and oppress Indigenous peoples. But we needed to involve a much larger portion of the community to achieve what needed to be achieved, because it was a thing for all of us. It wasn’t just a thing for Black fellas. It was for all Australians.”

Tranby College and land rights

After the NSW BLF was taken over by Victorian official Norm Gallagher in 1975 Cookie could no longer get a job in the building industry.

From there he became involved as an advocate for Tranby College, an education co-operative in Glebe, where he eventually became the first Indigenous general secretary.

At Tranby, Cookie also used his organising skills to advocate for Aboriginal education and around issues like Black deaths in custody, land rights and the Stolen Generations.

Cookie used his union networks to secure funding for the college and bring in a diverse range of teachers and learning programs, where Aboriginal students and unionists were able to develop their own organising skills and abilities, as well as form networks of their own. Here Cookie eventually established the Trade Union Committee for Aboriginal Rights (TUCAR).

TUCAR functioned to connect unions to Aboriginal communities and campaigns, with the college often becoming a base for campaign activity, as with the 1988 Bicentennial Protest.

As part of the Black Defence Group, Cookie played a key role in organising the 1977 Land Rights Conference held in The Block.

This was a major turning point in the campaign for land rights, as it brought Aboriginal groups from different regions of NSW together to discuss the way forward.

The conference resulted in a demand for full-scale recognition of Aboriginal land rights and the establishment of a NSW Aboriginal Land Council, of which Cookie became chairperson.

Around this time Cookie was also involved in the Aboriginal Affairs Policy Committee within the NSW ALP. The committee successfully campaigned, with the support of trade unions, for land rights legislation from the NSW Labor government.

While the Land Rights Act that resulted in 1983 was a disappointment, it did allow limited claims over Crown land that was not already in use and the transfer of Reserve land to Aboriginal Lands Councils.

The land rights campaign employed a range of strategies, including street demonstrations and bush meetings, and worked directly with regional Aboriginal communities.

It employed a similar principle to the rank-and-file democracy of the BLF, where activists directly listened to Aboriginal communities about their needs.

As Cookie put it: “The older people would say: ‘This is what you have to do.’ And all we did was to do their bidding. It wasn’t us jumping up and down and saying: ‘We’re going to get you land rights, and this is the way we’re going to do it.’ It was them telling us what to do!”

Cookie was the kind of person who avoided the limelight and instead worked to bring others with him, always encouraging them along the way.

Cookie was seen as someone who was able to work past personal feuds in order to gather alliances—the kind of person who not only holds the megaphone for others to speak, but who brings the megaphone and all the people out to listen.

Kevin Cook passed away in 2015, after a long battle with emphysema. The lessons he learnt as a militant unionist in the BLF and the networks across the union movement he developed there allowed him to become a staunch advocate for Aboriginal rights.

He was a living expression of the power to bring change that can come through linking Aboriginal struggles to the working class movement.

Read more in the book by Kevin Cook and Heather Goodall, Making Change Happen: Black and White Activists talk to Kevin Cook about Aboriginal, Union and Liberation Politics, available to download for free.