Privatisation has caused the crisis in the power industry, writes Chris Breen

Tony Abbott ran for election in 2013 promising lower power prices. But after four years of Coalition government power prices are higher than ever.

Now Malcolm Turnbull is promising “strong action” to address prices and ensure reliability.

The Coalition has tried to blame renewables, and state bans on coal seam gas mining for the price rises, but this is a lie. The fundamental cause of increasing power prices has been privatisation. This has happened at the same time as market madness has been allowed to quadruple domestic gas prices.

The government could entirely fix the power problem with price regulation, re-nationalisation, and direct government investment in renewable energy.

Gas crisis

The big gas companies have been exposed as price gouging in the domestic market. Two official reports showed there would actually be shortfalls in domestic supply over the next two years.

Turnbull has been able to force gas companies to provide enough gas for domestic use. But there is no guarantee on prices.

It turns out the shortfall is not the product of any lack of gas, but the refusal of gas companies to sell on the domestic market, in an effort to keep prices high. They have even been selling excess gas on the international spot market for lower prices than they charge domestically, restricting supply.

The result, as business journalist Ian Verrender has written is that, “Gas prices haven’t just increased. They have quadrupled. And the tragedy is that Australia, with one of the greatest reserves of gas on the planet, now charges its households and businesses far more to use that energy than the countries to which we export.” And because gas is also used in some power plants, rising prices add to power price rises as well.

The problem began in 2009-10 when the Queensland government let multinational oil and gas companies build three large export terminals. Prior to this Australia’s gas was almost entirely produced for the domestic market. But since the price of gas on the international market was higher, this put upward pressure on domestic prices.

The LNG exporters even used cheap gas from Victoria and South Australia to fulfil their international contracts. In 2014 the direction of the Moomba to Sydney pipeline was reversed to feed the Queensland export terminals.

The Coalition’s call to increase supply through more Coal Seam Gas (CSG) mining won’t cut prices either. CSG fracking is much more expensive than mining conventional gas.

Power prices

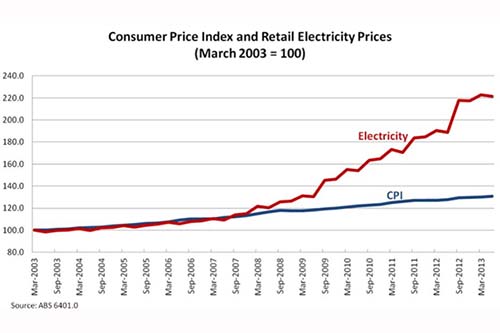

Ross Gittins writes in the Sydney Morning Herald, “The consumer price index shows retail electricity prices have doubled in real terms over the past decade”.

Ross Gittins writes in the Sydney Morning Herald, “The consumer price index shows retail electricity prices have doubled in real terms over the past decade”.

Rising electricity prices are a problem for workers and the poor. But they have also become a problem for big business. Rod Sims, Chairman of the Australian Consumer and Competition Commission (ACCC) says, “Energy affordability has gone from being a source of economic advantage for Australia to the opposite.”

His chief concern is for Australian business, but nonetheless he also points out, “our Retail Electricity Pricing Inquiry team heard stories of Australians having to ration electricity through winter, having to choose between paying medical bills and paying electricity bills, and having only a small amount to spend on food after rent and electricity is paid for.”

Privatisation is the real problem

According to Sims generation costs are responsible for only 19 per cent of the electricity price increases over the last decade. This is the result of the closure of coal power stations and the failure to invest in new power generation. Network costs are responsible for 41 per cent of the increase, and retail costs and margins for 24 per cent. These costs are essentially the fruits of privatisation.

Coalition claims about renewables being to blame don’t stack up. According to Sims they are responsible for just 16 per cent of prices rises over the last ten years.

Starting in the mid-1990s with Victoria, state governments first corporatised then wholly or partly sold off their electricity sectors. Queensland privatised the retail sector for electricity and gas in 2007 while maintaining public ownership of the network. NSW didn’t privatise its network until 2015. Nonetheless as corporatised entities they acted similarly to their fully privatised counterparts. South Australia, which has a fully privatised electricity industry, has the highest prices of any state.

Rising prices haven’t been the only bitter fruits of privatisation. Insufficient investment in maintenance contributed to the South Australian power blackout, the five week Auckland blackout of 1998 and the Longford gas explosion. Privatisation has also led to substantial job losses and attacks on unions. At the same time the Australia Institute found that the number of managers in the electricity sector grew from 6000 to 19,000 in the five years to 2012.

The new trend was hidden at first because privatisation came in the wake of the 1990-91 recession. Businesses going to the wall meant excess electricity production. This allowed surviving businesses to strike good deals in the early days of privatisation. However once retail privatisation was fully implemented and spare capacity reduced, consumers began to feel the full effect of rising prices.

Economist John Quiggin adds, “In the early years of the NEM [the National Electricity Market introduced in 1998], reductions in maintenance spending concealed this failure. When new investment became necessary in the early 2000s, the result was a dramatic upsurge in prices. This was primarily because the NEM regulatory system allowed rates of return on capital far higher than those needed to finance the system under public ownership.”

As a natural monopoly the electricity “market” is highly regulated, but in the interests of companies, not consumers. Profits for power companies are guaranteed by the Australian Energy Regulator which determines an “allowed rate of return”. This has led companies to regularly game the system.

Power companies notoriously over-invested in a “gold plated” network of poles and wires because they were guaranteed higher profits the more they spent.

A Senate inquiry found that costs passed onto consumers for operating the poles and wires doubled in NSW between 2007 and 2013, accounting for between 30 and 60 per cent of power bills.

Quiggin’s 2014 report on electricity privatisation also shows how power companies have claimed a need for high investment, and then under invested in any given period. He writes that in Victoria over a five year period, “The regulators expected to give returns of six to seven per cent, but the actual returns were closer to 10 per cent.”

The privatised retailers then add further costs on top. The Herald Sun writes, “Major electricity retailers have been grabbing almost $400 in gross margin per Victorian customer on average”, citing a report by the Australian Energy Market Commission. The same report shows, “gross margins were… a quarter of the average electricity price paid by residents.”

No wonder then that power company profits are booming. AGL Energy posted a 14.4 per cent increase in core profit to $802 million for the last financial year.

The Daily Telegraph writes that a Grattan Institute report, “shows profit margins for electricity retailers appear to be more than double what regulators traditionally consider to be fair.”

The problems of privatisation were not unforeseen. In 1948 a Royal Commission was set up by the conservative Playford government to examine the privately owned Adelaide Electric Supply Company. The commission found that over 24 years, two million pounds had been paid out unnecessarily in dividends and interest, and that “future capital costs at Treasury rates would result in reduced capital costs and lower charges”.

As a result the industry was nationalised.

Power stations

Today the problems remain. Every coal-fired generator in Australia was built with government money, because of the scale of investment required. Companies remain reluctant to invest on such a scale without guaranteed returns over a very long period.

The Coalition’s failure to agree on a climate policy to meet the targets it committed to at the Paris climate talks has not helped.

Nine coal-fired power stations have closed since 2012, and a number of others are reaching the end of their lives.

This investment problem has led to Turnbull’s bizarre proposals to subsidise the continued operation of the decrepit Liddell coal-fired power station after it scheduled closure date, and for the government to build a new coal-fired power station in North Queensland.

What we really need is a plan for government investment in renewable energy with storage. This is entirely feasible, as the 100 megawatt battery Elon Musk is building in South Australia, and concentrated solar thermal power stations with storage operating in Spain and South Africa.

The NBN was effectively a renationalisation to deal with the same investment problems in telecommunications, but the mess of the electricity sector alongside climate politics makes Turnbull’s dilemma much greater.

Labor leader Bill Shorten rightly said in an ABC radio interview recently that, “There is no doubt that privatisation has been a big problem… we’ve lost control of prices, and we’re seeing that the profit of large companies is being put ahead of the needs of consumers and business.”

The problem however is what to do about it. Shorten has ruled out nationalisation.

Labor and The Greens should be campaigning for price regulation and re-nationalisation. Their inability to see beyond the market, including clinging to forms of carbon pricing, allows the Coalition to get away with posing as concerned about rising prices, when they are responsible for them.

Direct government investment in renewable energy could reduce emissions, create jobs, and lower prices. Price regulation could similarly cut electricity prices. Electricity is an essential service, like health care and education. We can pay for it through taxing the rich.