Russia’s invasion that crushed the mass movement for political reform in Czechoslovakia in 1968 showed the reality of Stalinism in Eastern Europe, argues Miro Sandev

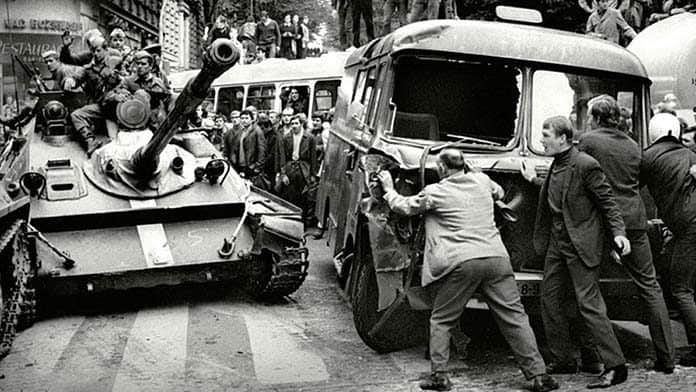

In August 1968, Russian tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia, putting an end to the Prague Spring; a brief period of democratisation and open discussion by writers and journalists that had broken through the gloom and repression of the authoritarian regime.

The Prague Spring movement rattled the Stalinist regime in Czechoslovakia, but the Russian tanks that had crushed the Hungarian revolution in 1956, again exposed the brutality of the USSR’s empire and its refusal to tolerate even mild democratic reforms.

The Russian invasion, and the resistance to it, played a key part in the development of genuinely revolutionary politics and the new left in 1968, that breathed life into the slogan, “Neither Washington nor Moscow”.

After the Second World War, the major powers had carved the world into two spheres of influence. The West was dominated by the US and its nuclear umbrella. Russia gained much of Eastern Europe incorporating East Germany, Albania, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Poland. These states were economically and politically dominated by Russia, revealing it to be an imperialist power just like the US.

None of these countries experienced a socialist revolution. Instead Russia simply installed pro-Moscow regimes and called them “socialist” states.

In Czechoslovakia in 1948, the local communist party did not smash the existing state structure. Assisted by the threat of the Red Army, it simply took it over in a coup. Communist party ministers, already part of a coalition government, secured control of the police force and used it to shut down all other political parties.

The new regime was state capitalist, just like the regime established in the USSR in the late 1920s when Stalin came to power. The Communist Party and the state bureaucracy it installed became the new ruling class. In Czechoslovakia 80 per cent of industry had been nationalised even before the coup. This increased to 95 per cent afterwards. But none of it was under workers’ control—state bureaucrats were the new bosses.

As in the rest of the Eastern Bloc, the regime built an authoritarian police state where any deviation from the Stalinist orthodoxy was swiftly repressed through military police, the courts and prison camps. Protesting, striking and any independent political activity outside the communist party was totally outlawed, just like in the USSR. Despite the repression, resistance periodically exploded, in East Germany in 1953, and in Poland and Hungary in 1956.

Economic crisis

Czechoslovakia was one of the most repressive of the Stalinist states, lorded over by the party secretary Antonín Novotny. The economy was harnessed to the USSR’s effort to compete economically and militarily with the Western powers, forcing them to attack workers’ conditions.

Czechoslovakia had an economic boom in the 1950s, taking advantage of its advanced industry to sell engineering equipment to the rest of Eastern Europe. There were substantial rises in real wages. But in the 1960s things began to change. The old markets for its industrial products shrank as other countries in Eastern Europe began to produce their own heavy machinery.

By 1963 the country experienced a recession. Economic reformers amongst the bureaucracy attempted to solve this by eliminating inefficient firms. But the result was that most workers saw real wages stagnate or fall, as inflation exploded. The reformers blamed Novotny and the old bureaucrats, arguing they had stifled the reforms.

A faction fight emerged in the bureaucracy between the old guard and the reformers. Both sides felt compelled to look outside the bureaucracy for wider social support.

Prominent writers began openly criticising Novotny. Then students took their chance to protest, with thousands marching in Prague against the poor condition of student housing. The brutal repression of the demonstration by the police only further radicalised the campuses.

The reformers were able to oust Novotny in January 1968 and form a new government headed by Alexander Dubček. They pushed through reforms including freedom of speech and association, the right to travel to Western countries and an end to the arbitrary arrests by security forces. They also pushed market mechanisms like closing down uneconomic firms, which threatened job losses. The reformers hoped to establish a revised version of Stalinism. But in doing so they opened a space for a much more radical critique of the system.

There was an outpouring of open criticism of government policy known as the Prague Spring. Dissident writers and journalist published articles; the state censors asked for their jobs to be done away with and ministers were grilled on television about their failings. Leading bureaucrats were forced to resign their posts. Meetings and debates were held outside of the control of the Communist Party for the first time and new independent political organisations sprang up.

However most of the intellectuals involved believed that they were still living in some kind of workers’ state which had to be reformed, rather than overthrown. Others concluded that workers’ revolutions would always lead to totalitarianism. Both perspectives were demobilising. A clear understanding that the 1948 coup was in no sense a workers’ revolution was necessary to have any faith in successful working class action in the future.

Meanwhile, workers began to step up their militancy. There were growing numbers of meetings, strikes, and resolutions from the shop floor. Wage claims were put forward. Strikes won improved conditions and forced the resignation of managers. By June 1968, workers had won increases in pensions and maternity and children’s allowances, as well as a reduction in the working week.

Some workers were drawing conclusions that led them to align themselves with the more radical intellectuals. Workers Committees for the Defence of the Freedom of the Press were formed in a number of factories. The new party leadership around Dubcek however saw the workers’ militancy as a threat, not just to old-guard Stalinism, but also to their own newly-won control over the country.

Invasion

The leaders of the USSR were also increasingly alarmed about where the Prague Spring was headed. In August they, alongside reliable Eastern Bloc allies, invaded with 200,000 troops. Within three or four hours all the main airports, frontier posts, cities and towns were dominated by thousands of Russian tanks. The Dubcek leadership was arrested and flown to Moscow.

As tanks rolled into Prague, hundreds of thousands of protesters occupied the streets. They confronted the invading troops, engaged them in debate, blocked their entry into buildings and removed street signs to confuse them. Workers held a series of sporadic strikes. While there was no armed resistance, this mass passive resistance helped demoralise the invading armies.

Dubcek’s faction eventually convinced the USSR that they alone could keep the Czech state machine functioning. The Kremlin released him and returned him to Prague, where he announced that the newly-won freedoms had to be wound back. He proposed a treaty legalising the occupation, tightening up censorship and control over the police and sacking those who had broadcast anti-occupation material.

Dubcek’s concessions were met with mass opposition. A resolution carried by 40,000 autoworkers called them “a shameful capitulation”. Mass worker and student demonstrations shook the country in November, January and at the end of March 1969. Huge crowds demonstrated against the Russians. Collaboration grew and students and workers carried strike resolutions.

As the regime split and under pressure from the workers, the formerly tightly state-controlled trade unions could no longer suppress strikes. But the trade union leaders were more concerned to direct the struggle into support for the reformers, like Smrkovsky, than to organise independently of them. If there was a choice between abandoning reform completely or being removed by the Russians, they chose to abandon reforms.

The million-strong metal workers’ union, the miners and the builders all threatened strike action if Smrkovsky or other reformers were removed from office. But Smrkovsky told his supporters to drop their resistance. He issued a grovelling apology to the Stalinist old guard admitting his errors.

In the first months of 1969 there were two rival sources of power, the Russian army and the trade unions. But the reformers were more concerned with their own positions in the state machine and were not about to lead the struggle that was needed.

For their part, the workers continued to look to people who were incapable of leading them—Smrkovsky and the trade union bureaucrats. An independent network of workers’ councils, able to lead the mass strike action needed to expel the Russian troops and defend the reforms, did not exist.

The result was that the energy and the anger of the workers quickly dissipated and the bureaucracy wound back the new freedoms.

Despite its eventual defeat, the Prague Spring had a profound impact. In Eastern Europe, two years later, mass strikes rocked Poland and forced the state bosses to withdraw price increases. The mass movements for democratisation gave people a taste of freedom that they wouldn’t forget. This resurfaced in the struggles that ended the state capitalist regimes in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

The images broadcast to the world of workers and students rising up against the Russian army split many Communist Parties around the world, weakening the hold of Stalinism on the Western Left.

In Australia, the Communist Party leadership publicly condemned the invasion, but a pro-Russian minority split away a few years later to form the pro-Russian Socialist Party of Australia.

In 1968, the world caught fire in Eastern Europe too. In January 1968, around the world, millions had gained an understanding of US imperialism as they watched the Tet offensive in Vietnam and saw the world’s greatest military power humbled in the streets of Saigon itself. In August, illusions that Russia and its look-a-like states were socialist were crushed under the tracks of the Russian tanks that stifled the Prague Spring.

The lessons of 1968 are just as pertinent 50 years later. The Prague Spring has given its name to the Arab Spring and the Iraqi Spring for the same reasons—brutally repressive governments have been challenged by struggle from below; and in those struggles we’ve seen the possibility of the socialism from below that Marx always advocated.