The American Communist Party’s work in the 1930s showed how it is possible to win white workers to the fight against racist oppression, argues Adam Adelpour

The Trump Presidency has opened an era where an openly racist bigot is the head of state in the world’s most powerful nation. The US has a deep legacy of racism through its history of slavery and segregation. But this history also holds important lessons about how to defeat racism.

The US Communist Party’s (CPUSA) anti-racist work in the Great Depression is one of the most important examples.

The CPUSA’s involvement in the Scottsboro Boys’ campaign in the 1930s and the Pittsburgh miners’ strike in 1931 are both classic examples of anti-racist struggle that warrant close examination. By fusing together anti-racist and economic class struggles the CPUSA was able to build an incredibly forceful vehicle for anti-racism.

Their anti-racist work was ultimately undermined by their support for the policies dictated by Stalin’s Russia. But what shone in that work remains of use to us today.

Many commentators and activists attributed Trump’s victory to a “whitelash”. According to this view white voters elected a racist because they feared racial progress as a threat to the benefits that racism supposedly affords whites.

One prominent example is Brittany Packnett, one of Time magazine’s “12 New Faces of Black Leadership” in 2015. She responded to Trump’s election win by saying, “White people handed us Donald Trump” and “… at the end of the day, 10 out of 10 white people benefit from white supremacy.”

This brand of anti-racism shares some common assumptions that are important to unpack. If it is accepted that all white people enjoy some benefit from racist oppression it follows that they have a stake in maintaining it.

Such a view forecloses the possibility of fighting racism on a united working class basis. It leads to a focus on black-only organising (often called “autonomous organising”), and an easy slide into the idea that all blacks have a common interest, whether they are millionaires and powerful political figures or people living in poverty. It can also lead to an inward looking focus on interpersonal anti-racism and retreat into “safe spaces”, since racism seems so insurmountable.

By contrast the history of the CPUSA in the 1930s shows how racism amongst white workers can be fought. It vindicates the Marxist view that racism, despite its real material effects, is a form of false consciousness pushed from above by the ruling class.

Racism is a tactic to divide in order to rule and incorporate in order to exploit. As such, struggles to economically advance the whole working class and struggles against racist oppression mutually strengthen each other. Racism must be confronted through radical tactics, unity and revolutionary class politics.

Context

The CPUSA was formed as a result of the Russian Revolution in 1917. The Socialist Party split, with the left majority of the party declaring its support for Lenin and the Bolsheviks.

From an anti-racist perspective this was highly significant. The Bolsheviks were defined by their support for national liberation struggles, movements for self-determination and the struggles of the oppressed.

This contrasted sharply with the right-wing of the US Socialist party who didn’t support anti-colonial movements at all. From 1917 the Bolsheviks had granted self-determination to oppressed nationalities and rights to minorities. Jews who were routinely killed in pogroms under the Tsar were found in prominent positions in the Soviet government; the most well-known being Leon Trotsky, one of the key leaders of the revolution.

An important but small section of black radicals in the US saw what the Bolsheviks had done in Russia and drew the conclusion that revolutionary working class politics was the only way to end racism.

They joined the US Communist Party and provided its first nucleus of leading black members in the 1920s—people like Cyril Briggs, James Ford and Harry Haywood.

The early CPUSA had to fight racism even within its own ranks. For example, when Harry Haywood decided to join the Communist Party in 1922, his brother urged him to temporarily join another all black revolutionary organisation called the African Blood Brotherhood instead. He said that the Southside CPUSA branch was too racist.

Such stories were typical. In this period the actual anti-racist work of the CPUSA was farmed out to a particular department rather than being seen as the duty of every member. This ensured racism festered.

The Comintern

The push that shifted the CPUSA decisively towards black struggle came from the Communist International, or Comintern.

The Comintern was set up by the Bolsheviks in 1919 to encourage the spread of revolutionary socialist politics. It had immense influence on the Communist Parties around the world like the CPUSA.

In 1928 the Comintern effectively decreed that the CPUSA should call for a separate black state in the US South and racial equality and integration in the North. Black members initially found this ludicrous as no one within the black population in the US was calling for this.

This “Black Belt theory”, as it was known, was deeply confused. However, by putting black struggle in terms of national liberation it also hammered home the centrality of anti-racist struggle to the socialist revolution.

National liberation had been central to the victory of the Russian Revolution. Under the rubric of the “Black Belt theory” the liberation of black people would be no less central to revolution in the US. This made it much harder for the CPUSA to treat black struggle as a side issue.

The Scottsboro boys

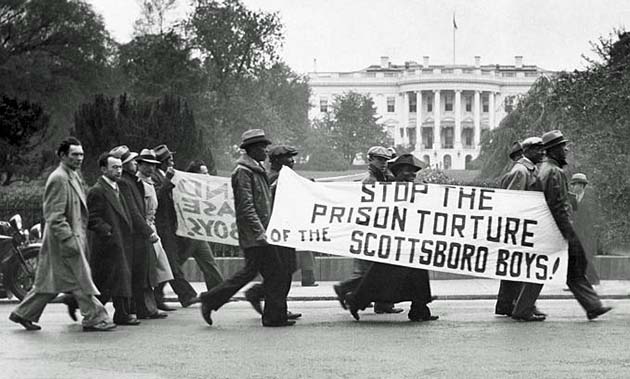

Shortly after this the Communist Party launched its most famous anti-racist initiative—the campaign to free the Scottsboro boys. The campaign began in 1931 and aimed to free nine young black men falsely accused of raping two white women and sentenced to death in an Alabama court. The arrest and sentencing was a racist police frame-up of a type common at the time. One of the alleged victims actually admitted in a retrial that the incident never took place.

As a result of repeated appeals a single black person was included in the jury and eventually charges against four of the boys were dropped. The others received prison time, but escaped death sentences. All of them were eventually pardoned; the last three pardons were as recent as 2013.

The Communist Party’s involvement in the case saw them openly contending for a position in the leadership of black struggles in the US. The leading black rights organisation at the time was the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It aimed to stop lynchings, gain voting rights and end segregation. However, it was based on the black middle class, employed legal methods rather than mass mobilisation and stayed away from militant tactics.

When the Scottsboro boys’ trial began the NAACP wanted nothing to do with the case. They ignored it because the accused boys were poor and working class. The NAACP felt that associating themselves with such riff-raff in a controversial case would only serve to tarnish their middle class respectability.

The Communist Party was able to win widespread black sympathy through its campaign of street marches in major cities, rallies in the segregated South and a strident demand for the boys’ immediate release. The NAACP quickly felt its preeminence was threatened and wanted in. They tried to gain control of the campaign, arguing that, “Communist involvement in the case would only hamper the proper conduct of the defense.” They also claimed that demonstrations antagonised Alabama public opinion, as did the demand for the boys’ immediate release. In contrast the CPUSA said they would “give the boys the best possible legal defence in the capitalist courts, but at the same time to emphasise… that the boys can only be saved by the pressure of millions of workers, coloured and white, behind the defense in the courts.”

The fact that the Communist Party was the only racially integrated political organisation in the US was an important strength. They had an almost unique ability to mobilise working class whites for black issues. However, this was initially used against them by political opponents.

When the CPUSA called the first Scottsboro marches in Harlem in 1931 mainly white workers turned up. This accurately reflected their membership at the time. The black papers called it a “white invasion” and denounced blacks that joined as “cannon fodder for a white party”. However, in the end the approach of integrated organisation, radicalism and working class unity was vindicated. It made it harder for police to isolate black protesters, made mobilisations broader and the community support for the campaign stronger. Soon thousands of black workers on the Harlem Scottsboro marches outnumbered white workers ten to one.

Confronted with such a tide of support for the Communist-led campaign, the NAACP was never able to gain control. The CPUSA led years of militant struggle which stopped the executions and saw most of the boys eventually freed. Over the period of the campaign the black membership of the party exploded from 1000 in 1930 to 5000 in 1939.

Class war in the mines

Another valuable example of the CPUSA’s anti-racist organising in the period is the Pittsburgh Miners’ Strike in 1931. It vividly demonstrated how the CPUSA successfully fought for unity amongst workers divided by racism. They did this by fusing together anti-racist and working class politics.

In the lead up to 1931 the major miners’ union had been smashed after a year-long strike. The conditions for miners were deteriorating rapidly and the Communist Party affiliated miners’ union had stepped into the wreckage. They lead a strike of 42,000 miners in the Pittsburgh area to re-establish basic pay and conditions.

The miners’ slogans at the time testify to the dire situation; one such slogan was, “As Well to Starve while Fighting as to Starve Working”.

Six thousand of the miners were black. In some areas blacks had come up from the South many years earlier, were well established and tended to hold the leading positions in the unions. Unlike the recent European migrants who did a lot of the mining work, these black workers could speak English. In such areas blacks were leading the strike. But in other areas, like in Pricedale, black workers had been brought in as strike breakers just five years earlier and were uniformly refusing to come out on strike.

Harry Haywood was sent to help organise in Pricedale. As a black Communist his unenviable task was to lead a strike of white miners who faced a large minority of scabs who were exclusively black. It was a racially charged situation.

A big part of why the black workers weren’t coming out was racism. The company housing for miners was segregated, and there had been racist incidents in the previous strike. Haywood described the rank-and-file leader of the miners in this area, Cutt Grant, as afflicted with “the white chauvinist illness”.

Haywood recounts a telling experience at a rally of the strikers. Cutt Grant was chairing the rally and introduced the white speakers enthusiastically. But his tone changed when it came time to introduce Haywood. Grant made a show of introducing him with extreme reluctance, as if to apologise to the racists in the crowd for the speaker being black. Racist white miners referred to Haywood as the “party nigger”.

But this entrenched racism was fought, not passively accepted. Haywood managed to convince Cutt Grant the only way out of the impasse was to have a big meeting about the Scottsboro Boys. Thousands came out to hear the famous black orator Richard B. Moore speak. Large numbers of black workers turned up after previously shunning union events in Pricedale.

Haywood recounts the profound effect the meeting had on Grant. Moore’s speech hammered home the links between the Scottsboro Boys’ case and the miners’ strike and illuminated the way racism works to divide and rule.

According to Haywood, after seeing black and white workers united in their loud applause for the speech, Cutt Grant approached Haywood and poured his heart out about how impressed he was. Purged of his racism he joined the CPUSA the next day—the same day that the black workers joined the strike. Although the strike was eventually defeated it was a tremendous example of how unity could be forged and racism fought in the most difficult circumstances.

Similar stories played out in factories, mines and department stores across the country. In this period everywhere there was division, racism and segregated unions, the Communist Party lead serious anti-racist struggle. A decade later black membership in the unions had increased five times over.

Conclusion

The work of the CPUSA in the early 1930s demonstrated the strength radical class politics could offer in the fight against racism. The CPUSA went from the margins of black life to leading the defining anti-racist campaign of the era over the Scottsboro boys. Likewise, its battle against racism in the unions showed the power of unity in action and dealt a serious blow to the pervasive racism in the US workers’ movement.

But the ability of the CPUSA to realise this potential was undone by its Stalinist politics. From the mid-1930s the CPUSA followed the “popular front” policies imposed on the Communist parties around the world by Stalinist Russia, and embraced people like President Franklin D. Roosevelt as allies.

This meant watering down their anti-racism—they even opposed a march on Washington against segregation to curry favour with the Democrats. This fitted with Stalin’s project of building alliances with capitalist governments against Germany.

In 1939 the CPUSA lurched the other way and had to explain why they were supporting the Hitler-Stalin pact. Predictably, when Germany invaded Russia the CPUSA became cheerleaders for Roosevelt again and even supported the internment of Americans of Japanese descent during the war.

The rapid degeneration of the CPUSA’s anti-racist work was a tragedy. Had a consistently revolutionary organisation on the scale of the CPUSA existed come the upsurge of struggle in the late 1960s and 1970s it could have had an extraordinary impact.

But the potential that was on display in the early 1930s should still inspire us today. Radical class politics and systematic party organisation were indispensable anti-racist tools on the streets of Alabama and in the mines of Pittsburgh.

It will require nothing less to confront the bigotry of a Trump Presidency or the kind of racist, state sanctioned torture we saw in Australia’s Don Dale juvenile prison. Then, as now, racism can be beaten.

Further reading

Communists in Harlem During the Great Depression by Mark Naison (2004)

Black Liberation and Socialism by Ahmed Shawki (2006)

Black Bolshevik: Autobiography of an Afro-American Communist by Harry Haywood (1978)