One hundred years since its founding, there are key lessons from the role the Communist Party played in the militant union movement, writes Judy McVey, despite their flawed politics

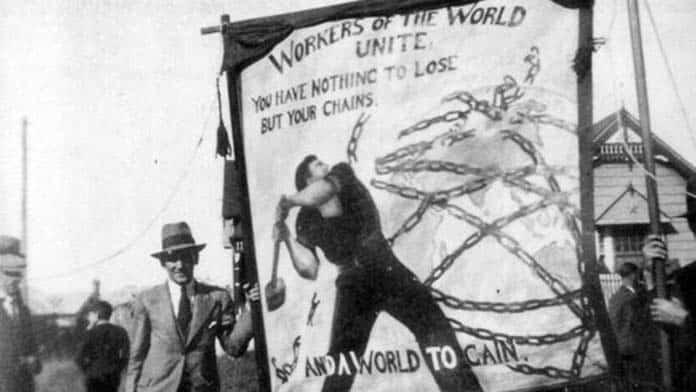

Inspired by the 1917 Russian Revolution, 26 people met in Sydney on 30 October 1920 to establish the Communist Party of Australia (CPA).

They came from two main groups: those associated with the Industrial Workers of the World and the One Big Union project, and members of pre-existing socialist groups hostile to the reformism of the Labor Party.

Based on the trade union bureaucracy, the Australian Labor Party had mass support amongst the working class.

While it had succeeded in winning enough seats in parliament to form government earlier than similar parties in Europe, its leaders had repeatedly betrayed working class people, especially during the First World War when they failed to defend living standards and pushed for conscription, despite enormous opposition in the union movement.

The Communist Party was based on the model of Lenin and the Russian Bolshevik Party, a revolutionary socialist party organised separately from reformist parties like the Labor Party.

The Bolsheviks had led the first workers’ revolution in Russia and argued that socialists had to organise within the unions and the class struggle, and that socialism was only possible through a revolution against parliament and the state, rather than trying to use it in workers’ interests.

The CPA became the largest socialist organisation Australia has seen. By the end of the Second World War, its membership reached its high point of around 20,000, with nearly 50 per cent of the delegates at the ACTU Congress, and a base among militant workers.

The party’s best period was in the Depression years of the 1930s, when it organised militant struggles among the unemployed and in the trade unions.

When the Arbitration Court, the equivalent of the Fair Work Commission of today, imposed a 10 per cent wage cut in 1931, the ACTU did almost nothing to fight it.

With a federal Labor government presiding over these savage cuts and little opposition from union leaders, the party’s denunciations of the Labor Party struck a chord.

CPA members formed a Militant Minority Movement within the unions to organise resistance.

The party grew significantly to 3000 members by 1934, with its first dramatic political successes among the unemployed.

They won increased unemployment payments through staging “dole strikes” on work for the dole projects such as the Melbourne Shrine. A strike over wages at Como was led by a rank and file committee of 40 men and women. Wives organised social functions, collected money and food, wrote articles and led militant actions.

As unemployment rose to 30 per cent, similar militant defiance was applied to fight fascists and stop evictions. The famous battle between 40 police and 18 communists at 143 Union St Newtown (Sydney) resulted in injuries caused by bullets and batons on one side, against iron bars, chairs, and stones.

In the unions, the CPA’s emphasis on rank-and-file control of disputes and militant industrial action helped build key trade unions, particularly in mining, clerical, engineering and manufacturing.

Central to their success were the committees of shop stewards (shop committees), combining union delegates from multiple unions across a workplace or industry, which built unity at the rank and file level, an important lever in negotiations and strikes.

The party also took on racism and sexism. The CPA was a leading force in this period for women’s rights and equal pay. They challenged White Australia and built solidarity with Aboriginal people’s struggles, linking political and industrial action.

Stalinism

But the party suffered an enormous political weakness. Its support for Stalinism and belief that Russia remained a socialist society without exploitation and oppression led the party to dismiss atrocities like Stalin’s show trials and labour camps, and defend Russia’s every action.

Stalin’s rise as dictator in the late 1920s saw Russia undergo a counter-revolution, establishing a state capitalist society locked in imperialist competition with the West.

The original revolutionary and socialist traditions of the Bolshevik Party were abandoned.

Stalin also imposed his own control over the Communist Parties worldwide, dictating local strategies according to needs of Russian foreign policy.

The CPA itself imposed an authoritarian regime, where dissidents were disciplined or expelled.

Initially Stalin imposed a wildly ultra-left Third Period strategy.

The Labor Parties were attacked as fascist and the Communists isolated themselves from the rest of the labour movement.

With the rise to power of genuine fascism in Germany, Stalin feared that Russia faced invasion.

So the Communist Parties back-flipped, arguing for the widest possible unity against fascism. But this extended to forming alliances even with right-wing parties.

Eventually the “Movement Against War and Fascism” became a Popular Front and was used to shore up alliances with anti-fascist governments.

This meant the defence of the nation against certain fascist powers—Germany, Italy and later Japan.

The result in Australia was to undermine independent working class politics and drag the Communist Party to the right, in order to cement alliances with Labor Party politicians, progressive intellectuals and ministers of religion. From this point “left nationalism” became a key element of the CPA’s politics.

After Russia joined the Allies in the Second World War, the CPA became the most enthusiastic supporter of the Australian war effort. Its members worked to smother class struggle and discipline workers to accept sacrifice.

For example, they tried to prevent a huge strike wave of thousands of women workers over equal pay, undermining a struggle which took another 25 years to put back on the agenda.

Over time, the credibility of Russia as any kind of socialist alternative unravelled.

In 1956, USSR President Khrushchev dropped a bombshell, denouncing many of Stalin’s actions. The same year revolutionary workers’ councils in Hungary were put down with Russian troops.

The majority eventually tried to “de-Stalinise” the party. In August 1968 the party publicly opposed the USSR’s decision to send troops to crush the Prague Spring revolt in Eastern Europe.

Ardent supporters of Stalin left to found the China-aligned Maoists in 1963, followed by USSR supporters who founded the Socialist Party of Australia in 1971.

But in rejecting Stalinism, the CPA simply embraced the same kind of parliamentary reformist strategy as the Labor Party. It had drifted a long way from the revolutionary Marxist politics of Lenin and the Bolsheviks.

Union influence

Although it began to decline after the war, and the defeat of the 1949 coal miners’ strike, the party had won the leadership of a number of trade unions, and retained a base of thousands of key union militants and delegates.

The CPA was central to most important union campaigns, and led the battle to win back the right to strike.

When a union official refused to pay fines under the ‘Penal Powers’ and was jailed in May 1969, nearly one million workers walked out on strike—making the laws a dead letter.

Communists in the unions played an important role in the movement against the Vietnam War, including the huge ‘stop work to stop the war’ rallies in May 1970. CPA officials like Jack Mundey were behind the green bans in Sydney and beyond.

They helped support the Gurindji strike at Wave Hill, which became a defining struggle in the fight for land rights, organising speaking tours and collections across workplaces nationwide.

Shop committees were the backbone of wages campaigns which by 1974 saw the highest strike figures ever (over six million strike days were lost, in a population of 12 million), which between 1965-75, delivered a real redistribution of wealth to workers, when company profits as a share of GDP fell from a historic level of 15 per cent to 11 per cent.

But the growing number of union leaders in the party also led to problems. Communist union officials increasingly relied on bureaucratic control of unions, rather than maintaining the strong independent rank and file organisation in the unions that had been the party’s strength in the 1930s.

The CPA regarded labour movement leaders who sold out struggles simply as bad individuals who could be replaced.

They did not understand the way that taking a role in the union bureaucracy exerts a conservatising influence on union leaders.

CPA union officials became key collaborators on the Labor Party’s Accord with the unions in the 1980s, which produced a severe weakening of trade union power and organisation and led to collapse in union membership that lingers today.

The Australian working class had experienced important victories because of the actions of socialist leaders in the CPA, but the end result of the party’s drift to the right and embrace of reformism delivered a historic defeat for the working class movement. The experience added up to betrayal.

The CPA’s Stalinist politics were a gross distortion of genuine Marxism.

Yet there is still much to learn from the history of working class struggles in Australia, where the Communist Party played a key role. Their work in the unions demonstrated one of the central tenets of Marxism—the power of working class action to not only win reforms but challenge capitalism itself.

Socialists today need to build a new revolutionary party based on genuine Marxist politics that can help lead not just the revival of workers’ struggle we need but a struggle to replace the capitalist system altogether.