On 15 April, Somali refugee Saif Ali was released from the Brisbane detention centre (BITA) to join his wife and son (Sabah and Sammi) living in the community in Brisbane. Saif had been in detention for almost eight years—six on Nauru, and two years in detention in Brisbane, first in the Kangaroo Point hotel prison, and then in BITA.

Saif was deliberately separated from his family in 2017, when Sabah and Sammi were brought from Nauru to Australia when Sammi became seriously ill shortly after his birth.

In June 2019, Saif was also transferred from Nauru to Australia, under the family reunion clause of the Medevac legislation, to join his family. But instead of family reunion, the government held Saif in closed detention for another two years. During that time, in October last year, in a moment of desperation, Saif attempted suicide in the Kangaroo Point hotel.

Saif is the only Medevac refugee to be released since February.

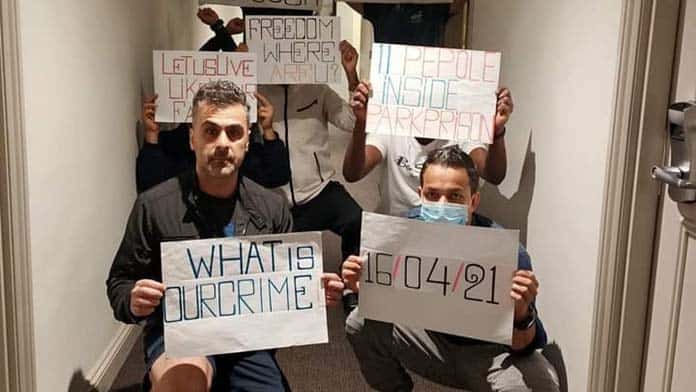

The day after Saif was released, the Kangaroo Point hotel prison was closed when the last 19 Medevac refugees there were hastily and forcibly moved to BITA. Three days later, 12 of the 19, along with another five Medevac refugees from BITA, were flown to detention in Melbourne.

The refugees had been held, without their property, in the BITA compound that is used for COVID quarantine accommodation for three days, before again being shifted to the Park Hotel in Melbourne.

“We are treated like cattle,” Mo, a Sudanese refugee now in BITA, told Solidarity.

The detention of the Medevac refugees has become a farce. While initially over 100 were freed, the releases stalled in February. Around 80 Medevac refugees, and another 33 people transferred from Nauru since the repeal of Medevac legislation, are still in detention.

In the High Court and the Federal Circuit Court, the government is strenuously defending the legal framework of the Migration Act, insisting that only those granted a visa have any right to live in the Australian community; and that unless the Minister grants a visa, the Commonwealth has an untrammeled power to indefinitely detain. To ram home its point, the government scheduled five refugees from Nauru to be forcibly removed from Australia on 15 April, although the flight was cancelled two days before the due date.

There is no “right to asylum” in the Migration Act. Successive Labor and Coalition governments have declared that no one sent to Nauru or PNG would ever be settled in Australia. But protest action has forced the government to bring the vast majority of those imprisoned offshore to the mainland.

We need to keep up the protests to win freedom, full rights to Centrelink and resettlement services and permanent protection for all those still held in the hotels and onshore detention centres—and fight to bring those still in PNG and Nauru to Australia.

Home Affairs to face charges over Villawood suicide

In an unprecedented move, the Department of Home Affairs and detention medical services provider International Health and Medical Services (IHMS) will face charges in the Downing Centre Local Court on 27 April under the Workplace Health and Safety Act (WHS Act) as a result of an Iraqi man’s suicide in the Villawood detention centre on 4 March, 2019.

It is alleged that Home Affairs and IHMS failed, “to comply with [its] health/safety duty and that exposed an individual to a risk of injury or death/serious injury”. The case has the potential to expose the details of abuse and medical neglect in detention that damages mental health and pushes detainees to take their own lives.

According to Monash University’s Australian Border Deaths Database, there have been 11 actual or suspected suicides in immigration detention since 1 January 2012 when the WHS Act commenced. There were another five suicides in Australia’s detention regime in just the few months between December 2010 and July 2011. The most recent suicide in Villawood was in December 2020.

The court case could run for years to tell us what we already know—the “factories of mental illness” have to close.

By Ian Rintoul