Respecting the sophistication and success of Indigenous societies doesn’t rely on pretending they were agricultural, argues Ian Rintoul

Peter Sutton and Keryn Walshe’s book Farmers or Hunter-Gatherers? has generated a storm of political debate. Many are concerned that the book is going to bolster the racist views of the likes of Andrew Bolt and Mark Latham and more generally set back the fight for rights and respect for Indigenous people in Australia.

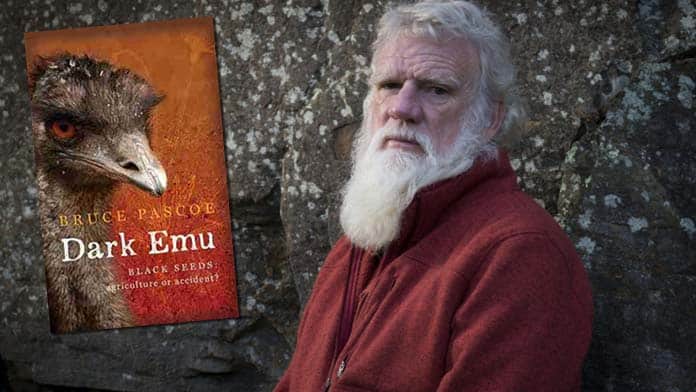

Yet the problems with Bruce Pascoe’s book Dark Emu were always there for anyone who was concerned to check Pascoe’s claims and references. Before Sutton’s book, others had already raised the problems with Pascoe’s argument that Aboriginal society was agricultural, including historian Tom Griffiths and Russell Marks in The Monthly.

So why, despite Dark Emu’s flaws, has it been so widely accepted?

For many people Dark Emu was a welcome antidote to the prevailing racism that regards Indigenous society as “primitive” and culturally backward. It is not hard to believe Pascoe’s argument that important achievements of pre-colonial Indigenous society have been suppressed, because so much of the history and present reality of Black Australia—the massacres, the stolen children, the stolen wages and the resistance—is still being hidden.

Pascoe’s book was uncritically welcomed because it celebrated the knowledge, sophistication, ingenuity and skill of Indigenous people. But it does so by trying to present them as agricultural societies, where people lived in permanently settled villages and tilled and planted the soil.

Pascoe is wrong about this. At its worst, Dark Emu uses selective evidence and exaggerated interpretations to paint a picture of Indigenous people being established agriculturalists. Sutton has assembled a formidable array of evidence against Dark Emu’s overall thesis.

The use of the term “hunter-gatherer” to describe Indigenous societies is historically loaded. Descriptions of hunter-gatherer societies have been tied up with the prevailing views that colonising powers were superior. But hunter-gatherer peoples across the world never just “forage and hunt”. The traditional Indigenous way of life in Australia was always far more than “simply wandering from plant to plant, kangaroo to kangaroo in a hapless opportunism”, as Pascoe describes what he calls the “accepted view”.

Sutton uses the terms “complex hunter-gatherer” and “hunter-gatherer plus” to describe the pre-1788 Indigenous way of life on this continent.

As Sutton correctly puts it, “Aboriginal people were practical and spiritual managers and modifiers of their environment, skilled hunters, adept fishers and trappers, and very botanically knowledgeable foragers who had long come to grips with the problems of making a living in a wide range of ecologies,” and further, “They were ecological agents who worked with the environment, rather than, usually, against it.”

The tragic irony is that, in Dark Emu’s attempt to celebrate Indigenous practices as “agricultural”, Pascoe ends up denigrating the way traditional Indigenous societies actually worked as “primitive”. Pascoe accepts and reinforces a social evolutionist conception of historical progress. This places hunter-gathers at the bottom and capitalism at the top, along with all the politically discriminatory connotations of what is socially advanced and civilised. To that extent, Pascoe himself is both a victim and a booster of the prevailing ruling class ideology.

The politics of Sutton

To counter Pascoe’s claim that the real history of Indigenous people has been hidden, Sutton has a chapter outlining books and documentaries produced over the last 50 years that have documented and celebrated Indigenous knowledge and sophistication.

But Sutton wilfully ignores the fact that the predominant view in Australian society is still that Indigenous culture is “backward”.

These ideas justified the initial genocide that established Australia. They continue to be fed by ingrained systemic discrimination and the relentless effort by politicians, supported by sections of the media, to blame Indigenous people and their culture for the problems inflicted by European colonisation and on-going dispossession.

Sutton’s book has been seized on by right-wing attack dogs such as Andrew Bolt and Mark Latham who thoroughly embrace ideas of white supremacy and see Western culture as superior. The blatant political agenda of Dark Emu’s conservative critics can be seen in Coalition candidate, and Bundjulung man, Warren Mundine’s, attack on Dark Emu, not out of concern for the facts of traditional Indigenous society, but for being “woke.”

Like Mark Latham, Sutton and Walshe have called for Dark Emu to be removed from schools.

It’s striking that Sutton has never been motivated to campaign against the more fundamental failure of the school system to educate children about the impact of colonisation on Indigenous people and their lands, and the “black history of White Australia”.

A review earlier this year found the current Australian curriculum failed to recognise that, “the First Peoples of Australia experienced colonisation as invasion and dispossession”.

This was too much for Liberal Education minister Alan Tudge who told Sky News he was “concerned” about the use of the word “invasion” and would “seek some changes”, saying “I don’t want students to be turned into activists.”

The idea that Aboriginal society is inherently primitive, violent and dysfunctional underpins the racist stereotypes, the discriminatory laws, and drives the police harassment and victim-blaming of policies like the Northern Territory Intervention.

Disgracefully, Sutton himself was an influential apologist for the NT Intervention. He has done his own share of peddling negative stereotypes, blaming Indigenous culture for the levels of community violence in his 2009 publication, The Politics of Suffering.

In Farmers or Hunter-Gatherers, Sutton cites his close relationships with Indigenous people across northern Australia to establish his bona fides, but he is silent on the intense oppression their communities face.

In the conclusion to the book, Sutton in fact lauds Native Title for recognising “Aboriginal people as the previous owners of the land”. But the idea that Indigenous knowledge and connections to land are valued in Australia is a farce. Sutton ignores completely the insidious role of the Native Title in legitimising dispossession, dividing communities and extinguishing claims to land.

Some have reacted to Sutton’s argument against Dark Emu by suspecting that his book is itself an attempt to continue to deny the level of skill that Indigenous land-managers actually had.

But recognising the skills of Indigenous society does not depend on portraying that society as agricultural. Pascoe’s argument actually gives political ground to the conservatives.

Pascoe goes so far to argue, “While we continue to think of Aboriginal people as having no construction skills it is easier to dismiss Aboriginal attachment to land. Moreover the insistence on using the hunter-gatherer label is prejudicial to the rights of Aboriginal people to land.”

Why “construction skills”, rather than the Indigenous societies’ intimate ecological knowledge and cultural connection with the land, should give Aboriginal people greater “claim” to the land can only be explained by Pascoe’s acceptance of social hierarchy—that being “more productive” (and more like the invader) is a basis for greater sympathy and greater political claim.

Pascoe asks, “Why don’t our hearts fill with wonder and pride,” when claiming that Indigenous people had domesticated grains for agriculture thousands of years ago.

But the real question is—why doesn’t Dark Emu think that our hearts should fill with wonder and pride at the ingenuity and intimate ecological knowledge developed by Indigenous peoples over tens of thousands of years to live sustainably with their land?

Agriculture and class society

For Marxists, what is significant about agricultural society is not any conception that it is more “advanced”, but that agriculture makes it possible for a society to produce a reliable, large-scale surplus of food which allowed a completely new way of organising society to develop. The beginnings of agriculture from around 11,000 ago have rightly been described as a revolution in social life that triggered rapid population growth, new forms of technology, religions and social attitudes.

This does not mean that traditional Indigenous societies existed in conditions of general impoverishment; those societies were egalitarian, and developed ways of resource management to improve the reliability of food supply.

The creation of a social surplus, however, is the necessary precondition for the development of social classes, and the beginning of the inequality and exploitation that inevitably emerges with the development of class society. A minority ruling class forms, that relies on, and has control over, the surplus.

Unlike many colonised societies that were agricultural, there was no Indigenous elite to be incorporated into the social structures established by the invasion of 1788. As an outpost of empire, Australian capitalism was initially based on the expansion of agriculture and farming; that expansion drove the genocide of the Aboriginal population as the colony relentlessly engulfed the continent.

The establishment of the Australian colonies and the subsequent development of Australian capitalism was founded on the violent and systematic dispossession of Indigenous societies. It is that stark reality and its bloody history that today’s ruling class cannot escape, and which gnaws at the legitimacy of the Australian state. The struggle for self-determination and land rights is an integral part of the struggle against Australian capitalism.

The problem with Dark Emu’s argument is that it ultimately undermines that struggle because it accepts and promotes the idea that the agricultural society brought by the invaders is indeed superior. Pascoe says, “to deny Aboriginal agriculture is the single greatest impediment to inter-cultural understanding”. Strangely, this seems to be tied up with Pascoe’s ideas that reconciliation can be advanced by the commercialisation of “Aboriginal food products”.

The European invasion smashed an egalitarian society and began a continuing process of environmental destruction. The on-going oppression of Indigenous people that denies them their land, and inflicts the poverty, the “gaps” in housing, health and education, and the deaths in custody is an on-going stain that marks the racist foundations of Australian capitalism.

The hope of ending Indigenous oppression and racism lies in a common struggle that links the struggle against oppression with the power of the working class to smash the chains of capitalism, and to forge a new egalitarian, socialist society.

Farmers or Hunter-Gatherers? The Dark Emu Debate

By Peter Sutton and Keryn Walshe