Paddy Gibson examines how racist government policies have led to the surge in Indigenous imprisonment and deaths in custody

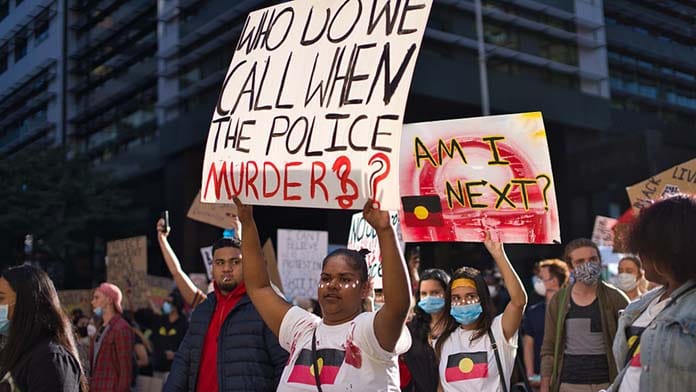

The Black Lives Matter movement that exploded onto the streets across the US in the wake of George’s Floyd’s murder has inspired some of the biggest protests against the killing of Aboriginal people in police and prison custody in Australia’s history.

There is nowhere in the world that needs a Black Lives Matter movement more than Australia. Indigenous people in this country are incarcerated more than anyone else on the planet and are ten times more likely to die in custody than non-Indigenous people.

These horrific numbers have massively increased since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCIADIC), which delivered its final report in 1991. This was the outcome of the last major wave of campaigning on this issue in the 1980s and there were high hopes it would deliver change.

Its final report said that the main reason for deaths in custody was that “too many Aboriginal people are in custody, too often”.

In 1991, an average 2140 Indigenous people were in prison. By the March quarter of 2020 however, a staggering 12,902 Indigenous people were in prison, an increase of over six times.

This can only be explained by the intensifying racism, poverty and over policing faced by Aboriginal people in all aspects of their lives.

Police forces across Australia perpetrated a genocide against Indigenous people during the initial colonisation of Australia.

Police had extraordinary powers to control Aboriginal lives throughout the “Protection” era in the 20th century. Hyper-surveillance and constant brutality have continued into the present day.

The Royal Commission called for “an end to domination and a return of control over their lives and communities to Aboriginal hands”.

But recent years have seen the complete opposite—a war on self-determination.

The most graphic expression of this was the NT Intervention in 2007, which introduced explicitly racist controls over Aboriginal life reminiscent of the “Protection” era.

Across Australia, Aboriginal controlled services have been systematically defunded, forced to toe the government line or broken up and replaced by mainstream agencies or NGOs.

Police and welfare agencies that forcibly remove Aboriginal children are given unprecedented budgets, while the Federal government has completely abandoned support for Aboriginal housing and employment programs and many remote communities have even had funding for essential services withdrawn.

Racist violence and neglect

Since RCIADIC reported in 1991, there have been 438 Indigenous deaths in custody, yet not a single police officer or prison guard has ever been held criminally liable.

Many of these deaths are the direct result of violence at the hands of authorities.

In November 2019, 19-year-old Warlpiri man Mr Walker was shot dead by police officer Zachary Rolfe, while resting at his grandmother’s house in the remote NT community of Yuendumu.

Walker’s bleeding body was dragged into a police station, where police locked themselves in for hours before heavily armed re-enforcements arrived by plane.

Protests began in Yuendumu that night, with young relatives making signs that read “Black Lives Matter”. This sparked an unprecedented wave of protest across NT communities, culminating in a convoy of more than 150 cars from Yuendumu to Alice Springs for a rally.

The night of the convoy, it was announced that Rolfe had been charged with murder.

Shortly after, the WA Department of Public Prosecutions announced that a police constable in WA would be charged with the shooting death of Yamitji woman Joyce Clarke in Geraldton in September 2019.

These charges are a breakthrough and a testament to the power of protest. A shameful history of acquittals of police, however, demonstrates there will need to be ongoing mobilisation for there to be any chance of conviction.

Racist negligence also routinely kills Aboriginal people in custody.

Tanya Day, a 55-year-old Yorta Yorta woman, was arrested after she fell asleep on a train from Echuca to Melbourne in 2017.

She was targeted due to racial profiling, arrested for being drunk in a public place and left to die after falling in her cell.

A courageous family-led campaign forced recognition by the Coroner that racism played a role in her arrest and police conduct been referred to the DPP to consider charges.

In NSW, the inquest into the death of 36-year-old Nathan Reynolds is set to begin in the spring. Nathan was left to die from an asthma attack in a minimum security prison.

Despite his asthma being well known, guards took 20 minutes to respond to his calls for help before calling a nurse.

It took 40 minutes before an ambulance was called. Nathan was dead by the time it arrived.

On 13 July, another Indigenous man, this time just 19 years old, died in custody in Acacia prison in WA in an apparent suicide. But it is the negligence of a racist system, that left him without the support he needed, that continually allows this to happen.

The inquest into the death of Tane Chatfield, which concluded in Sydney on 17 July, is likely to declare his death another suicide.

But Tane should have never been in prison. He had served two years on remand awaiting trial for a crime his family maintain he did not commit.

Continuing the momentum of the Black Lives Matter movement will be crucial to pushing for successful prosecutions over deaths in custody. And ending the violence and oppression suffered by Aboriginal people from police and the prison system is closely linked to the struggles to win back stolen land, to win self-determination and to end grinding poverty.

Ultimately, the prison walls must come down and the system that relies on racist police violence uprooted.

Chatfield family: ‘the prison system killed our son’

This statement was read by Nioka Chatfield on behalf of the family of Tane Chatfield following the coronial Inquest 17 July

On 20 September 2017 our lives were changed forever. Our son Tane had been on remand for two years in Tamworth prison for a crime he did not commit. Tane was 22 years old with one son. He was a proud Gamilaraay, Gumbaynggirr and Wakka Wakka man.

The night Tane was supposed to have broken the law, he was home in bed with his partner Merinda and his young son. But like so many thousands of Aboriginal people, he was thrown into prison without trial—a decision that would be a death sentence.

We have waited three years with no answers about our son’s death and this has taken a huge toll on our family. Why was the initial investigation done by Corrective Services themselves and by the police? We all know that these systems work to protect their own.

We need a completely independent body set up to carry out the immediate investigation into any death in custody. And in Aboriginal deaths in custody, our people must be centrally involved. The family must be given all information straight away and allowed to share our own experiences and views to inform the investigation.

Tane’s father Colin was in and out of prison for much of the time that the children were growing up. They were robbed of that time with their father. Colin suffered from terrible bashings, from psychological abuse, extreme racism and segregation.

Colin got to know about all the Corrective Service officers and had to be on guard the whole time, as you never knew when they would strike. Aboriginal inmates were targeted and were far more likely to be locked in segregation and Colin suffered this all the time. Colin’s cousin Douglas Henry Pitt was bashed and hung in the jail.

One thing that has been totally missing from this inquest is any understanding of Tane’s experience in the prison system. It hasn’t given any insight into the struggle of a young man on remand for two years who fought for his innocence. Just like his father, Tane too was bashed by guards. On many visits, and on phone calls, he would tell us of this treatment. Tane’s sister has even witnessed him being assaulted by guards when she went for a visit.

That’s why we say that the prison system killed our son. No matter what happened in that cell on the morning he was found. The constant pressure, the violence, being away from the family he loved, we saw him change after the time he spent inside. He was pushed to breaking point.

We don’t want any more men, women or children on remand in the NSW system because it can be a death sentence.

We have seen that Corrective Services staff and Justice Health staff breached policies and procedures. They assumed things about my boy without checking the proper paperwork. I believe that if the reports had been read, if my son was allowed to contact his family, or if I was contacted when Tane was first hospitalised the night before he died, I wouldn’t be standing here today without my son, we could have all been at home together as a family.

Aboriginal people are less than 3 per cent of the population. Here in NSW we are almost 30 per cent of the prison system. And more than one third of those prisoners are on remand—many will be found not guilty or won’t be sentenced to any time in prison at all. We are the most incarcerated people in the whole world. How much more blood does Australia want? What will it take to stop locking up and brutalising our people?

We say that the prison system itself is destructive and the bars must come down. There is no rehabilitation, there is no making society any safer. People have their mental health destroyed. They develop no skills and get no opportunities to better contribute to society. We say build communities not prisons.

We can see from the evidence in this inquest that Black Lives still don’t matter in the NSW prison system. We need change now and we need justice for Tane and everyone who has been killed in custody. We ask you all to join us in our fight to make that change.